|

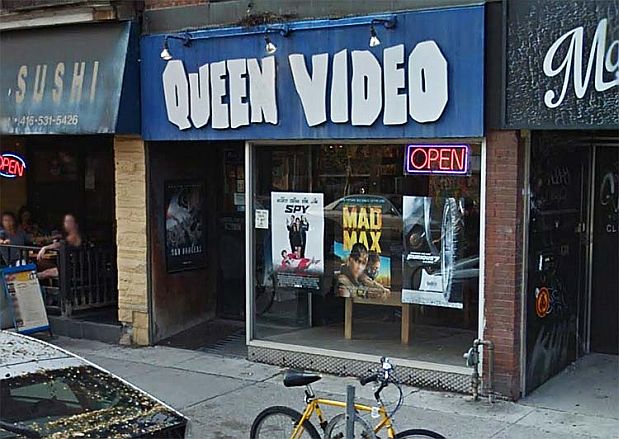

| Happier days at Queen Video in Toronto. |

The recent closing of the flagship store of Queen Video in Toronto, after nearly thirty-five years in business, was illuminating on so many levels, from what it augured for the future of film viewing at home to what people were most interested in snapping up as the store sold off most of its 50,000 titles (some were transferred to the still-existing Queen Video outlet, further north in the city). As I picked through the detritus of what was still left on the premises on Queen Video’s last day, after a 23-day sell off of stock when DVDs were down to $1 a pop, I was saddened that another great rental outlet was closing even and, more significantly, aware of what that closing actually meant.

Being there on Queen Video’s last day, after two previous visits when the stock was appreciably pricier – most DVDs began selling at $10 each, which for movies like Spotlight and the Israeli titles I covet and teach (Cup Final, To Take a Wife, Nina’s Tragedies) was already a sweet deal – I couldn’t help but notice what was gone and what was left. The Criterions, of course, were not to be seen – I got one two weeks earlier (when so many of them had already been purchased), Jan Troell’s fine Everlasting Moments, for $20, which is the cheapest one can hope for a used Criterion disc – and most of the Blu-rays were also sold. So were most major foreign language and American titles and the store’s ‘erotica’ section. Still on the shelves in great quantities on that final day were English-language comedies, an apt reminder that so few recent U.S. titles are of the calibre of a Groundhog Day or Tootsie, movies you want to own and re-watch; a surprisingly large of cache of documentaries, including major titles such as Bus 174 and Sharkwater (I wanted to buy those but those specific DVDs were MIA, not surprising when so much stock was being sold off. I did purchase No End in Sight and four other interesting docs though) and many horror movies, the genre least liked by the most people. Still, I found some interesting titles, besides the docs, including the recent film The Girl on the Train (La fille du RER) (2009), by talented French director André Téchiné (Rendez-vous, 1985; Le lieu du crime, 1986, My Favorite Season (Ma saison préférée) (1993), which I had not seen, as well as a French title with Daniel Auteuil and a quartet of films – Stage Beauty, Shattered Glass, Pour Elle (For Her) and Open Hearts – which I’ve always liked but never owned. I also took a shot at buying a number of obscure films I knew nothing about – hey the price was right! - from Germany, Thailand and Japan. (As I work my way through the 40-odd movies I bought at Queen Video, I’ll be reviewing and commenting on some of them in future posts.)

|

| Marlon Brando in Francis Ford Coppola's The Godfather (1972). |

Simply put, streaming can only let you view a fraction of the 50,000 DVD titles Queen Video rented out. According to a recent Globe and Mail article on streaming and digital restoration by Kate Taylor, Netflix Canada, the major legal streaming service, may only have a mere 4,000 movie titles at hand; Taylor found that the original The Manchurian Candidate, as well as classic 60s TV series The Avengers were among the titles that Netflix or iTunes didn’t carry. (Even illegal streaming doesn’t offer as many titles as are available physically.) Whatever the actual number – though from my perusal of the site, it seems accurate – this means if you purport to be a real film fan, you need to rent DVDs if you actually want to roam the depth and breadth of what exists. If, however, it’s all about the convenience of streaming and nothing else, and we live in a world where convenience, particularly online, is everything, then who cares if Queen Video or other outlets like The Film Buff go under? After all, you’re really more interested in ease of access to films, however comparatively few are at hand, than having access to as much cinematic variety as possible. There’s a music corollary to this, namely the rise in popularity of vinyl records, often at the expense of CDs. If you’re a music buff , who wants to own music and not stream it, and though you may prefer vinyl to CD – I don’t – I’d say you still need to buy CDs to augment your vinyl purchases as so much music is available only in the CD format. Yet I rarely if ever see anyone in the used and new CD/vinyl shops I frequent regularly, carrying armloads of both. For the most part, the vinyl folk only purchase vinyl, implying that it's less the music than the format that reigns supreme for them. (I’m not debating auditory quality of the respective formats here; I’d probably agree with Critic at Large’s Kevin Courrier, who knows whereof he speaks and buys both, that it depends on the specific album or musical genre - classical releases of the past, he opines, are often better on CD because the distracting pops and hisses on vinyl are now able to be excised.) In my case, price and space – CDs obviously take up less of it – are why I go with the CD format exclusively but, at least, I can posit that I’m not missing out on as much music because, so far, almost all music is still released on those little shiny discs.

The other factor in movie rentals, in person or online, is the fact that the younger demographic does not 1) know or care about film history and 2) isn’t interested in searching out the obscure or unknown on DVD. The former is why we’re getting unnecessary remakes like the upcoming Ghostbusters (an all female version) or Mad Max: Fury Road, which if we’re honest, was just a retread of the (superior) Max Max movie The Road Warrior (1982). The latter is why Howard Levman, owner of Queen Video, is quoted in the Kate Taylor piece as saying that the ratio of back catalogue rentals at his store to new release rentals had flipped from 80/20 in the past to the reverse today. He goes on to say, “Public tastes have changed. Young people aren’t interested in watching a Godard, a Kurosawa, a Sam Peckinpah from the 1970s,” adding that his rental of Kurosawa’s classic masterpiece Seven Samurai (1954) has declined to a few times a year from a few times a week. That’s major and, frankly, disturbing to me, and reminds me of something Canadian filmmaker Atom Egoyan (Remember) wrote a few years back about his then 17-year-old son Arshile and the film tastes of Arshile’s friends. By and large, they found, Egoyan wrote, The Godfather to be too slow and Pulp Fiction to be too complicated. Of course, Francis Coppola’s masterpiece and its sequel, The Godfather II, were made in an American Golden Age of cinema – the late 60s to late 70s more or less – when movies took the time to tell their stories. I’d venture that today Coppola would be told to shave The Godfather's opening wedding sequence, which runs almost half an hour and tells you everything you need to know about all the major characters in the rich, nuanced and complex film , to a third its length so as to get on to the next scene.

As for Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction, which is not a masterpiece by any means, its fractured narrative could only confuse someone who hadn’t seen its inventive like in the movies of Jean-Luc Godard (Breathless/À bout de souffle, Weekend) or Alain Resnais (Hiroshima, Mon Amour, Last Year at Marienbad/L'Année dernière à Marienbad), made thirty years so before Tarantino’s 1994 movie. And it’s not like Tarantino isn’t aware of whose footsteps he follows in; his production company A Band Apart Films is, after all, named after one of Godard’s (best) films.

|

| John Travolta and Samuel L Jackson in Quentin Tarantino's Pulp Fiction (1994). |

This resistance to innovation in movies and the corresponding lack of desire to discover new films and filmmakers isn’t entirely new. I worked in a video store back in the 90s, Revue Video, before DVD, when people’s interests generally replicated box office success; our weekly Top 40 rarely had any sleepers or neglected gems on it. But though we carried art house and foreign language films, our patrons weren’t so much movie geeks as individuals or couples or families who wanted an entertaining film to rent on a Saturday night. Stores like Queen Street Video were supposed to appeal to a more discerning, adventurous audience who liked, as often as not, to be challenged in the movies they rent. Yet, Queen Video’s flagship store is now gone and that means the few remaining video outlets, including Queen Video’s other store and fine rental establishments like Bay Street Video, another Toronto stalwart, are all that’s left for those of us who seek out unfamiliar fare to excite us. I’m not blameless here: I rarely rent movies for anything but teaching purposes as I’ve always been a purist intent on seeing movies on the big screen with whatever leisure time is left after that usually reserved for television viewing, another changing demographic that can make for another column in itself.

I will, however, and Queen Video’s closure adds new urgency to this, endeavour to now make an effort to rent movies that never played commercially or at all in Toronto as well as titles, often worthwhile, that went straight to DVD. Considering that only Criterion can be guaranteed to issue classic titles on DVD in the future, a tangible format that will eventually vanish – and major films like Jacques Rivette’s fantastic Celine and Julie Go Boating (Céline et Julie vont en bateau) (1974), Francesco Rosi’s masterful Illustrious Corpses (1976) and Satyajit Ray’s sublime Days and Nights in the Forest (1970), among important others, are still not available in that format in North America, time may be running out for anyone who wants to see certain, non-commercial, non - Hollywood titles, outside of cinematheques. Toronto’s rep houses don’t much show older movies, either – likely because film or digital prints are not available and because the culture of going to repertory or second-run houses has declined. (Levman found that many damaged or lost classic discs could not be re-acquired for his store as they were out of print, perhaps because the distributor saw no incentive to keep making them available.)

Toronto is lucky in this regard as, unlike many American cities, we still have major DVD rental outlets, used CD shops and used bookstores to frequent – though CD stock is being minimized in favour of vinyl, which still may not save those stores as the newer businesses trafficking solely in vinyl have the edge when it comes to attracting those buyers, and the independent bookstores have also begun to close as the rents rise and people prefer to stay home and order books online from Amazon. At this rate, the idea of browsing for books or DVDs or CDs will become a lost art and Toronto will join the culturally deprived mainstream. And that’s the greatest irony of all. We live in a time of more music and movies (and books) available to us than ever before. Increasingly, however, because of perceived convenience and sheer laziness, we’re seeking out less and less of it in the process. That’s something I think we’ll come to regret, but by then it may be too late as so many of the movies and albums we’ll want to watch or listen to will no longer be available – unless we want to acquire them for exorbitant prices on eBay or Amazon.

No comments:

Post a Comment