|

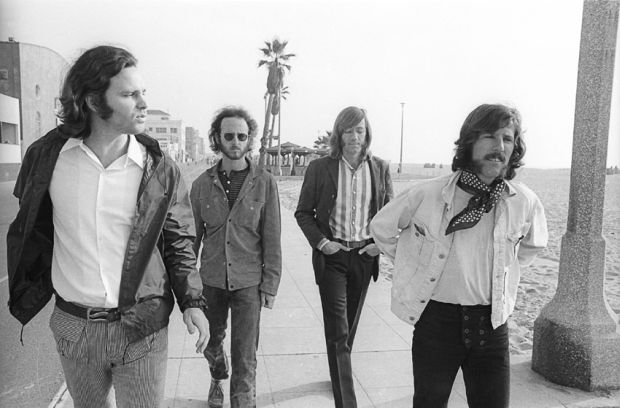

| The Doors, Venice Beach, CA, 1969 (Photo: Henry Diltz) |

On January 4, 1967, The Doors debuted with their self-titled album on Elektra records. To celebrate the 50th anniversary this year, Rhino, in association with Elektra (Warner Bros), has released a 3 CD + LP limited edition collection featuring the album in mono on LP and CD, the stereo mix and a previously unreleased live performance from the Matrix club recorded in March 1967.

The Doors’ recordings have never been out of print and, considering the number of hits they had that peppered FM radio after Jim Morrison’s death in 1971, their music continues to engage us. Their history has been well maintained in countless books, magazine articles, a feature film by Oliver Stone and documentaries. The most recent doc, 2014's People Are Strange, droopily narrated by Johnny Depp, is a chronological visual study of the group’s earliest years, their growing fan base and outrageous concerts. Consequently, Morrison, the charismatic, chemically altered front man, remains one of the most popular singers in the history of rock and, in my opinion, would remain so even if he hadn’t died in 1971 at the age of 27. His songwriting was unconventional, serious and rooted in the most peculiar places. He wasn’t a Florida beach boy dreaming about girls in bikinis or interested in drag racing. This was a guy who read the poetry of William Blake and the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche while dabbling in the mescaline-infused writings of Aldous Huxley, whose book The Doors of Perception suggested the name of Morrison’s band. All this by the time he finished high school and enrolled in the UCLA film school.

The diverse musical background of The Doors should never be underestimated. Unlike most groups from the mid-sixties who were influenced by their predecessors such as Chuck Berry, The Doors didn’t play in cover bands to learn technique and evolve into something bigger like The Rolling Stones or The Beatles. What makes The Doors stand out is the wider scope of their collective musical influences and their fearless experiments in music. Elvin Jones, who played drums for John Coltrane, heavily influenced John Densmore. Robbie Krieger studied flamenco music exclusively while developing a technique that did not include a guitar pick. The group didn’t have a bass player, only keyboardist Ray Manzarek, whose left-hand technique mastered the bottom end of the music. They loved to improvise and Jim Morrison’s often erratic stage presence fueled their work until it came crashing to an end.

I’ve been interested in hearing mono mix recordings for several years, since

the release of The Beatles In Mono in

2009. Those recordings from 1962 to 1968 offered some new sonic insights

into the band’s great music. It was the same for the Miles Davis in Mono box set of his Columbia recordings, released in 2013. The Davis recordings are sublime compared to their stereo

counterparts. Unfortunately I can’t say the same about The Doors mono mix. Rhino offers nothing in the way of

source material information for the mono version and, to my ear, did nothing

to re-master that original source recording. I’m not even sure if this is a

mix-down from stereo or a simply a new pressing of the original mono mix.

No technical information is offered in the box set. That said, The Doors album is packaged handsomely, using the heavier

vinyl LP to balance the 3 CDs in the gatefold jacket. The only change is

the speed correction of “Light My Fire” and “The End,” which were issued a

half tone slower in 1967. (Engineer Bruce Botnick explains that error in the liner notes.)

I’ve been interested in hearing mono mix recordings for several years, since

the release of The Beatles In Mono in

2009. Those recordings from 1962 to 1968 offered some new sonic insights

into the band’s great music. It was the same for the Miles Davis in Mono box set of his Columbia recordings, released in 2013. The Davis recordings are sublime compared to their stereo

counterparts. Unfortunately I can’t say the same about The Doors mono mix. Rhino offers nothing in the way of

source material information for the mono version and, to my ear, did nothing

to re-master that original source recording. I’m not even sure if this is a

mix-down from stereo or a simply a new pressing of the original mono mix.

No technical information is offered in the box set. That said, The Doors album is packaged handsomely, using the heavier

vinyl LP to balance the 3 CDs in the gatefold jacket. The only change is

the speed correction of “Light My Fire” and “The End,” which were issued a

half tone slower in 1967. (Engineer Bruce Botnick explains that error in the liner notes.)

As a result, I was really challenged to find something new in this album beyond my first impressions when I discovered The Doors in my teens. For me, the band had an elaborate and eclectic mix of music on their debut and they weren’t like anybody else on the airwaves at the time. “Light My Fire” was the big hit, but it took months to find an audience. In fact, the first version I heard of this remarkable song was by José Feliciano, whose stunning and passionate recording on RCA was a bigger hit than The Doors at the time. Eventually the original version became the definitive and lasting recording, but for a time Feliciano’s was the gold-standard performance for me.

The Doors album is a mix of bossa nova, blues, R&B and Indian ragas, all presented via the prism of a cabaret stage show. Since The Doors were based in the cultural lifestyle of southern California, LSD, marijuana and alcohol were constant companions. Morrison was a heavy drinker and frequent day tripper long before they went into the studio in August 1966 to record their first album over five days. (The recording of “The End,” in two takes, features Morrison under the spell of acid.) In the liner notes for this anniversary release, Botnick tells the story of his participation and what it was like to work with Morrison: “The vocalist [was] this very shy guy who had never been in a recording studio, and was barely able to face and audience while on stage.” To calm the young singer’s nerves, Botnick showed him the microphone he would use, a Telefunken U47 that was also used to record the voice of Frank Sinatra, one of Jim Morrison’s favourite singers. On the stereo mix CD included in this set, we get Morrison double-tracked and up front. In a way he becomes larger than life with his shifting and often seductive vocals. The mono mix flattens all of that excitement and shrinks the size and volume of the band’s presentation. In other words, we get a better sense of the street-wise music of which The Doors built their early career. What I can say about listening to the mono version is that the songs are more confrontational. When they recorded their debut in the summer of 1966, they already had dozens of club dates under their collective belts including a regular stint at L.A.’s Whiskey a Go Go, one of the most important clubs for new acts to gain a wider audience. The performance from The Matrix bears this out.

Nevertheless the mono mix best succeeds with the shorter songs on the album. “Break On Through” jumps out of the speakers with a lot more pep. The same can be said about “Soul Kitchen,” “Take It As It Comes” and “Back Door Man,” which reflect how tight this band became once they figured out what kind of band they wanted to be. The group’s passion and focus and the edgy, dangerous quality of to their music was impossible to resist and the mono mix brings out these qualities easily. But the longer tracks, “Light My Fire” and especially the 11-minute opus “The End,” lose their mystique and theatricality. The stereo version of “The End” is much better in bringing out the Indian raga drone that carries the tune. It’s far more mystical and weird because it captures that strange, mysterious sound The Doors presented without superficiality. They demanded your attention and the stereo mix grabs your ears and imagination much more effectively. It also cushions the confrontational nature of the songs, a tension that was hard to resist from the band in a live performance. So while I admire Rhino for issuing this album upon its 50th birthday, this particular set isn’t essential to your collection. All you need is the stereo re-issue of 2007 (CD) or 2012 (Vinyl) or the original ’67 LP to get the full effect.

– John Corcelli is a music critic, broadcast/producer, and musician. He is the author of Frank Zappa FAQ: All That’s Left to Know About the Father of Invention (Backbeat Books, 2016) now available.

No comments:

Post a Comment