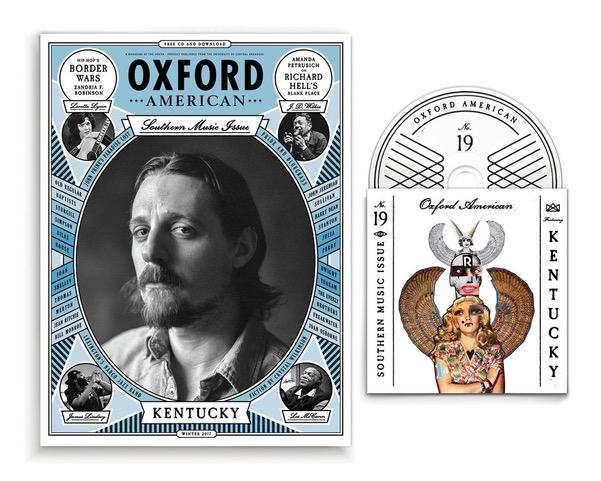

This year’s 19th annual music issue of The Oxford American features alt-country musician Sturgill Simpson on the cover with a defiant, rebel-like smirk suggesting the music from his home state, Kentucky, is back with an in-your-face attitude. But the cover portrait is nothing but a gentle ruse because this 99th issue is an ambitious collection of essays about finding “the middle ground,” that is, where artists remove themselves from their physical environment to find their voice while acknowledging the pull of home. The Kentucky music scene, like most of the southern United States, is shaped by the rural geography and its urban centers, which is why this particular issue is so passionate about discussing the contrasts between the socioeconomic backgrounds of the musicians who call the state home.

I was particularly impressed with Ronni Lundy’s personal memoir about Dwight Yoakam’s early years and how the veteran country artist needed to leave Kentucky and head west to California as an escape from his uninspired home. But as Yoakam matured and started making a name for himself in the highly competitive country-music scene, he felt the need to return to Kentucky in spirit, in order to “[float] somewhere in between – that place in the middle. The place to be heard.” For me, his song “A Thousand Miles From Nowhere” from 1992 best reflects Yoakam’s philosophical point. Lundy’s story, from the perspective of a music journalist, is about “The Hillbilly Cat” and it’s a gem among the many great essays in the magazine.

Amanda Petrusich’s interesting and appreciative piece on Richard Hell, “Blank Place,” stands out in this year’s issue. Petrusich tracked down the former leader of the rock bands Television and The Voidoids, at his New York apartment to follow up on her story. What’s remarkable about Hell is how he’s kept his focus as an artist. He’s never sought the “middle ground” in his music, but what he felt as kid growing up in Lexington, Kentucky hasn’t changed very much. Now 67, Hell is just as much an outlier today as he was at the age of 23 while active in the New York punk scene of the seventies. As he puts it, “Kids who come to New York to have adventures and make a life for themselves; they’re choosing to leave their boring origins.” That may have been his incentive as a reckless teen, but today Hell says, “I’m just restless and uncomfortable.”

This issue is mostly about country and bluegrass musicians but I was particularly struck by the streetwise sense of Les McCann, jazz musician and singer, who gets a short but effective profile by Harmony Holiday (her real name!). McCann was born and raised in the Jim Crow South of the 1940s. As Holiday puts it, “McCann’s approach to life as a teenager was proof that no amount of discrimination could undermine black culture, a culture propelled by collective improvisation as expressed through music.” It’s one of several observations that stand out in the piece. The second one is Holiday’s assessment about the black musicians who enlisted in the military in order to continue playing music. To her, it was a “perverse notion . . . since they were subsequently trained to defend a country that was fighting to maintain their systemic oppression.” But after talking to McCann and re-evaluating his commitment to the music first, she concludes that it was “a miracle wherein the war effort helped foster some of the most loving music the country has ever known and enabled.” McCann’s most famous song is the politically charged “Compared To What” from the 1969 live album called Swiss Movement, with tenor sax player, Eddie Harris, also from Kentucky. Considering the political conditions in the United States right now, McCann says, “I don’t know why they’re [the radio] not playing it now. Bump the Trump.”

|

| The Les McCann Trio in 1962: Les McCann, Herbie Lewis, and Ron Jefferson. |

I was especially moved by J.D. Daniels's piece on Jimmy Raney (1927-1995). It’s an eloquent ode to the Louisville guitarist, who recorded with sax legend Stan Getz and vibe player Red Norvo, plus put out a few solo records. Daniels's praise for Raney is often poetic, and it encompasses the larger world. He puts his best prose forward when describing Raney’s sound and style within the band: “In his silence, in his patience, in his elegance, in his respect, he left room for others, knowing they were his brothers and sisters, as real as he was, and they needed and deserved time and space in this world we all must share.” I’ve never read anything as beautiful about a musician as that sentence.

This issue also features a great story about The Everly Brothers called “Living Too Close to the Ground,” by Will Stephenson, who talks about his interest in the band and how it framed his interest in the art of Ray Johnson, whose collage called Untitled (Moticos with Everly Brothers)(1953/1994) inspired him despite its appearance: “[I] found it gruesome and inexplicable and almost certainly the best commentary on the group I’d ever seen. Like their music, it’s filled with shadowy figures and incoherent qualities.” An image of Johnson’s work accompanies Stephenson’s essay that complements the story effectively.

No magazine dedicated to the music of Kentucky would be complete without an article about Loretta Lynn, one of the state’s most famous artists. In Marianne Worthington’s “Hey Loretta!” we get a treatise on Lynn’s down-to-earth style and high praise for her coiffure, which the writer calls “a beehive-mullet.” For Worthington, who admired Lynn as a kid growing up in Knoxville, Tennessee, it was an inspired look: “For me, Loretta Lynn’s hair signaled a self-assured determination. You had to be both poised and assertive to pull off such a hairstyle, right?” Her piece goes on to describe the particular pressures Lynn had to endure from the sexist Nashville promoters who wanted to “polish her up” and mess with her diction and dialect. Fortunately, Lynn had an ally in Owen Bradley, the great record producer, who encouraged her to sing and sound like herself. Worthington goes on to discuss her relationship with Lynn’s songs as she matured: “I had grown up enough to realize the sexual tension that spiced up her lyrics.” It’s a loving tribute to Lynn in spite of the often-challenging moments when the artist’s politics conflict with her own. (Lynn publicly supported Trump.) As Worthington sees it, “the music always wins."

Last but not least, among the many sentimental yet unaffected essays is Leesa Cross-Smith’s “Ain’t Half Bad” about country music’s current radical, Sturgill Simpson. The author praises Simpson’s outlaw style from a unique perspective as a “musical-taste unicorn: me a black woman who knows and loves country music.” Cross-Smith blends her cultural background, growing up in Kentucky in a really personal way as she defends her right to exist and to be “black” with the generational lineage to prove it. Hers is an excellent cultural essay that compares a novelist with a songwriter who both rooted in the Bluegrass State.

This accompanying CD is a thoughtful juried collection of 79 minutes' worth of music ranging from bluegrass artists such as Brett Ratliff to the fabulous Booker Orchestra from 1927, whose music “has been almost completely obscured by time.” It’s a great album supplemented by a terrific magazine in the service of its most prized musicians. Great writing is certainly a highlight in every Oxford American and this issue is no exception.

– John Corcelli is a music critic, broadcast/producer, and musician. John is also the author of Frank Zappa FAQ: All That’s Left To Know About The Father of Invention (Backbeat Books).

No comments:

Post a Comment