|

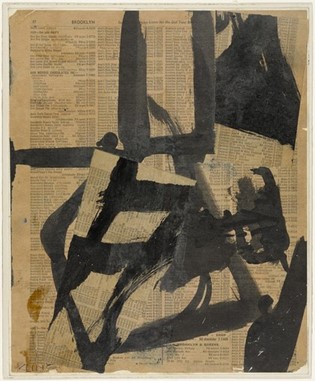

| Franz Kline, Untitled, New York, 1952. |

“The cultural environment is merely the reflection of what is in us, and if the cultural environment has changed, then something in us must have changed.” – Suzy Gablik, 2004.

Whenever I consider these two subjects and themes, which is something I tend to do several times a week, I can’t help thinking that the reason so many avant-garde artists either practice Buddhism, or are at least deeply influenced by its vibe, is the basic and simple fact that even though it’s more than two and a half millennia old, the philosophy that originated in India and swiftly moved to the East and West already was and still is a highly experimental venture in its own right. Few things, after all, could be more radical and avant than the notion that there is actually no tangible, abiding and independent self, and that impermanence is really the only guiding principle upon which we can construct a code of conduct grounded in compassion.

The 20th century. It was already a uniquely experimental time in history for a wide variety of reasons, some of them industrial, some of them economic, and many of them social and cultural. But the avant-garde principles by which a new and daring kind of art would be produced, in absolutely every medium of expression almost simultaneously, were largely due to a confluence of certain seminal ideas associated with modernity. Central notions such as secularism, pluralism and individualism formed the crux of those impactful variables at the heart of what we now think of as modernism. Ironically, such notions are also at the heart of both ancient and contemporary Buddhist practice, in addition to that of the disruption of conventional thinking.

But it will be my contention in this exploration of the dramatic impact and influences of eastern Buddhist philosophy, as well as those embodied meanings contained in art works upon the avant-garde tendency of the West, that it is a connection so pronounced as to be almost invisible. Indeed, this realization has often prompted me to remark that there is no East or West in dreams. Perhaps one of the most salient insights about the challenges presented by both the vanguard art expressions and also the inherently risky reflections implicit in the primary Buddhist principle of emptiness (the absence of an independent and consistent self) is contained in the charming comment made by French artist Marcel Duchamp, in dialogue with Pierre Cabanne, back in 1966: “There is no solution to the problem because there is no problem.”

|

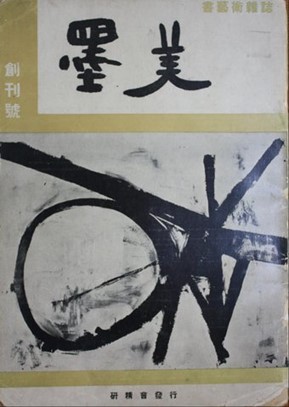

| Cover of first issue of Bokubi Magazine, with Franz Kline art, 1951. |

Even though I’m partial to the edges explored by avant-garde art and culture, that doesn’t mean I necessarily have an answer to the question of what it all means, any more than as a longtime Zen practitioner I have the answer to the puzzling questions posed by the paradox of consciousness without a self. But in the same way that technology transformed our understanding of what “Art” might be, the counterintuitive insights of Buddhism altered our grasp of what both the self and philosophy might be. And at a certain point in art history, as we’ll see, they both intersected and overlapped in a dramatic and entertaining manner.

This collision was perhaps totally inevitable, given that both sides of this apparent polarity were drastic and revolutionary departures from conventional thinking, one about the purpose and function of art and the other about the nature and potential of consciousness. Both were also subtle but powerful psychologies, one delving into the limits of beauty and reason and the other excavating the causes and effects of impermanence. Modernist art rejected centuries of assumptions about what was sacred in the illusion of realism, while Buddhism, especially its later stages such as Chan, Zen and Dzogchen, was a robust rejection of centuries of traditional Hindu and Vedic presumptions about various gods, goddesses, and those spiritual forces used to try and come into contact with them.

Most forcefully perhaps, Buddhism was an evidence-based practice, even in its earliest inception. It provided counterintuitive behavioural alternatives that had already plainly established a quantum-like spiritual science of integrated wholeness that had yet to even be imagined by the West’s eventual tardy grasp of relativity and the unified field realm some two millennia later. Thus both endeavours, relativity-based science and subjectivity-based meditation, were already each radical experimental ventures into an unknown domain which sanctified, each in its own unique manner, the spontaneity of abstraction and the technology of pure intuition.

Duchamp, one of the four most important and influential artists of the last century, and another French exemplar of pure vanguard aesthetics, also inadvertently draws our attention to one of the key strategies for approaching art that the average viewer, or listener, or reader, may at first find somewhat daunting. And he does it in his typically cheeky Gallic manner, which is disarming and reassuring at the same time: by employing perhaps the most Buddhist insight available to those confronted by, and often even taken off guard by, the avant-garde tradition.

First: there is no problem. This art can’t really hurt you, no matter how exotic it may look or sound. Not even the profoundly puzzling art of Yoko Ono can ever hurt you, so lighten up and enjoy the brevity of life. Second, there is, therefore, no solution, so stop trying to find a way to solve what doesn’t really need solving. That much is already inherently Zen-like. Immediate consequence? You can start actually enjoying weird art, books, theatre, music, poetry, films, novels and buildings which you might at one time have found rather forbidding, to say the least. True, this new art isn’t Rembrandt or Shakespeare or Bach, but that’s the whole point, since it is precisely the creative degree zero towards which most classicism was traveling all along.

We now all inhabit an iconosphere of global proportions at the very event horizon of images, one heralded by the arrival of the dialectical image. Photography, films, television and computers have had major impacts on perceptions of visual art, and indeed, reproducibility has completely altered our shared visual awareness of the world we live in and perhaps even of our reality itself. Investigating the nature of reality, not realism but reality, was the main tenet of modernism and the avant-garde. In this regard there was already a surprisingly shared vision and mutual impulse between the practitioners of both Buddhism, another profoundly dialectical idea, and the avant-garde tendency: the shock of the new.

We still need to further explore the foundations of modernism’s most important concept: discontinuity, especially in light of the era after modernism, in which we are supposedly living. But, you see, there is nothing after modernism: there are only late and later modernism—which is also the most vital point I want to make in this narrative. Another thing is also certain, the paradox of discontinuity is that even it still occurs in a manner which strikes us as being synchronistic. Paradoxically, discontinuity was and is at the heart of the Buddhist strategy to derail the customary recursive thought patterns by allowing us to focus on their obvious dissolution into the overall space of mind.

And Buddhism, just as with the avant-garde tendency in art, focuses on the individual, although largely in a contemplative manner that is supposed to prove that, in reality, there is no individual. But either way, in both traditions, the individual, relative, and subjective mind was paramount. Or so the art and music, literature and poetry, culture and design of the dynasty of dissonance appeared to declare. Thus the adage, “There is no solution to the problem because there is no problem.”

Einstein showed us that mass can be deliberately converted into energy, with devastating results. So, too, can classical aesthetic principles be converted into modernist dissonance—luckily, with endlessly entertaining results. Those results are perfectly clear and obvious if we examine the way the artistic inheritors of Duchamp and John Cage’s creative breakthroughs in art and music have invested their precious legacy. For me, this is especially the case with Cage, whose early Zen-teaching encounters with D. T. Suzuki drastically altered his own life, and the entire course of the avant-garde, forever.

|

| American composer John Cage meets D.T. Suzuki, Tokyo, 1962 (Antronaut, Cage Trust) |

As we enjoy a look backward at the delightful accomplishments of Duchamp and Cage, among others, we are also able to look far forward. The present cultural moment affords us a wealth of artists situated similarly who are currently toiling in the rich creative fields first fertilized by those two saints at the turn of the mid-twentieth century. As we move cautiously past the second decade of the twenty-first century, we can still feel the strong echo of those artists who first made it possible to think not only outside the box, but outside of thought altogether.

We can appreciate them even more now because so many contemporary artists are now living and working in a future imagined and made possible by those two great precursors. Theirs is a future which is always still arriving. Buddhism, meanwhile, as most readers already know, and as others may hopefully discover, is much more focused on the permanent present. A good thing, since that’s the only time in which we ever actually exist.

|

| Black Reflections, Franz Kline, 1959. |

"The right art is purposeless, aimless. The more obstinately you try to learn how to shoot the arrow for the sake of hitting the target, the less you will succeed. I am an artist at living . . . my work of art is my life." – D.T. Suzuki.

In many ways, from the perspective of the established tenets embedded in its country of origin upon encountering the uniquely radical thought of Siddhartha Gautama, also known as Shakyamuni, sage of the Shakya clan, in what is now called Nepal, the first Buddhist in history was indeed a revolutionary and avant-garde figure. As is well known, though born of lofty rank to one of the ruling elites, and comfortable describing himself as a Kshatriya when he was addressing them as a presumptive Brahmin, he first discovered and then established a truly experimental non-theistic thought platform that rejected both asceticism and indulgence.

Indeed, he was so flexible in his teaching forms that he could address almost anyone in a context and conceptual framework capable of making the most sense at any given moment in time. The principles he espoused, now very well known globally, were also aligned in an alarming way with a relativistic and quantum form of thinking that was still two and a half millennia away form being ‘discovered’ by western science. He was thus able to discern the multi-faceted nature of reality in a manner that permitted him to see that matter didn’t actually exist, that it was merely a form of energy that had a higher or lower frequency or vibration, and hence capable of either being considered solid and physical or mental and spiritual.If we remember that the term avant-garde references the advance vanguard or reconnaissance brigade of troops, sent out in advance of the customary army in order to test the waters and clear their passage via information and intersession, then it’s not even outlandish to refer to Buddhism as an avant-garde practice. It is therefore even less surprising to learn how compatible the philosophy was with experimental and avant-garde artists of all stripes, for the simple reason that Buddhism is itself, by its very definitions, of which there are many, already radically avant-garde.

The notion of an ‘American Buddhism’ began to take rapid root in a culture that was itself founded on a kind of conceptually grand mythology that theoretically embraced all outsiders wishing to ‘become’ Americans. An important worldwide Buddhist conference was organized in San Francisco in 1915 by the Jodo Shinshu Mission and the first Soto Zen temple, Zenshuki, was created in Los Angeles in 1927. Most importantly for our narrative on the ideological interplay between the avant-garde and Buddhism, D.T. Suzuki, in 1950, began teaching Zen Buddhism, and his prolific writings strongly influenced the Beat movement of artists, among them most significantly Alan Watts, Gary Snyder and Allen Ginsberg.

Watts’ The Way of Zen and Ginsberg’s “Howl” in 1955 opened up the pathways between Yank experimenters and traditional Buddhist practice even further, along with Jack Kerouac’s own idiosyncratic amalgamation of eastern vibes in works such as The Dharma Bums. The intercultural garden was growing fast, with a second significant Suzuki, Shunruyu, a Soto Zen monk from a family of abbots, being the most influential influencer of American Buddhism during the 1960’s.

Many young artists of this period rejected the past, their own and their country’s, and plunged headlong into the whirling world of modern philosophy and experimental politics and philosophy suddenly available to their generation. Meaning-fatigue, the major ethos of the post-war period, as exemplified by its main exponents, Camus, Heidegger and Sartre, would also become the calling card of the Beat Generation, the crucial ’50’s proto-period of loosening up which immediately preceded the so-called Love Generation of the 60’s.

For these experimenters, both in the East and in the West, existentialism perfectly captured the essence of the troubling insights to which they had been prone since the calamity of war carnage, with its emphasis on raw being: our concrete existence in space and time, our aloneness in a world bereft of faith and the simple fact that, as complicated marvelously by intricately complex thinkers such as Sartre, that our existence precedes our essence. This last notion also shares a considerable parallel with Buddhism, which had partially already formed their collective character as artists: the fact that long before our personality or persona is formed (our essence), we are faced with the palpable evidence of our being in the world (our existence) and the challenges we encounter will be positive, negative, or neutral, depending on how we project ourselves into that world.As a matter of fact, it would later be the melting together of Zen-inspired insights with Existentialist-inspired observations, especially in the making of fragile art objects with seemingly apolitical content, which formed the basic Fluxus sensibility that has been most widely associated with the avant-garde’s own later mythology. Dore Ashton has remarked on a special gift a whole generation of Japanese artists in particular had for taking “their native traditions into their world views . . . in an exhausting quest for affirmation of their intuitive choices . . . and remaining faithful to certain tenets of the Existentialist movement: most particularly, the insistence that the individual exists vis-à-vis the other; that the human condition requires the making of something; the acknowledgement of reciprocity as a force in nature; and the fight against death, often equated with silence.”

This profound notion especially impacted the creative efforts of avant-gardists such as Cage, most famously perhaps in his notorious composition 4:33, and its four piano ‘movements’ consisting of no sounds. Kaido Kazu believes that the Japanese Neo-Dadaists differed from their American counterparts, though, because of their social and political concerns: “It is now clear that there was an underlying spirit of radicalism and anti-authoritarianism in post-war Japanese avant-garde art.” One example of what some perceive as their gnomic qualities, attitudes certainly shared by avant artists, then and today, was a preference for art-minus-art. The true Dada heritage from the years around the end of the First World War was known only from books, but some of the major players of the period were still alive and enjoying a new-found notoriety.

Duchamp, the éminence grise of the New York Dada tradition, Kazu affirmed, was very much on the minds of the young Japanese musicians around John Cage, for instance. Duchamp’s influence hovered over the more unorthodox Fluxus group in the early 1960’s, which, under the guidance of George Maciunas, announced themselves as an international force. These Zen-inspired groupings in New York, which tended to include all the arts, overflowing boundaries between theatrical performance and musical performance, poetry and music, painting and dancing, were aware of similar loose assemblies in Europe and Japan, and soon established active ties.

As characterized by Kazu to Japan Society curator Alexandra Munroe, “At the heart of nearly every happening, or performance, was the challenge to art itself, the testing of the limits and the Ubu-like urge to destroy everything in order to create something pure.” Searching for something pure and beyond limits, that could be the slogan for virtually all of the American cultural experiment in general, and the American arts vanguard in particular. And Eastern Buddhism in general, with Zen as a particular focal point, richly nourished the freshly-fueled hearty appetite for radical newness in postwar western art. Of special interest was a deep curiosity about one of the key pivots of all Buddhist thought: the Void.

The debate over the relationship of mid-century American art to East Asian art has been skewed by the obsessive scrutiny of a few famous names. Yet Fluxus, though international and utopian in its anti-commercial stance, had already been prefigured to some extent by the loosening up of cultural values in Japan just after its defeat. In 1950, Okamoto had also declared his own “theory of extreme contrasts” in a famous and influential article called “The Non-Sense, the Laugh,” a tongue-in-cheek celebration of the new wave of mutual experimentation between East and West:

It is thanks to the resolution of staying with non-sense that the real sense appears. It is precisely the absence of all sense that reflects an acute social conscience. It is possible that seriousness is not serious and a joke is not merely a joke. Utter nonsense may have more power to change social reality than seriousness. What we call the serious joke may be the foundation of art.Apart from being an amalgam of many Zen Buddhist precepts and an embrace of the uncertainties inherent in postwar thinking, this new anti-art stance was also a daring acceptance of modernist ideas embedded in the European avant-garde ever since the turn of the century. Subsequently, the inherent Yankee sense of liberation from the past spurred the dialogic experiments ever onward.

And like everything else it imported and improved upon, America quickly became the capital of the avant-garde, after it borrowed the idea from Europe and confidently expanded it up to truly American-scale dreams. Even though it was first initiated in a Europe reeling from two World Wars on its own lands, the notion of a radical vanguard cultural edge was obviously tailor-made for the key utopian American sensibility. It wasn’t just a mythically open frontier aggressively waiting for its own expansion, after a little serious real estate acquisition, that is, since its own edgy genesis as a idealist zone was available to anyone and everyone for their own personal expansion too.

I tend to agree with the insights of the pop art and music historian Ian Macdonald, always an astute observer of the cultural ferment of the 60’s, in his assessment of its core function and its impact. The profound influence of Fluxus was and is often still is largely subterranean, but it’s still with us nonetheless:

This type of art was designed to change the way its beholders experienced reality—to disrupt the habit-induced hierarchy of incoming sense data, rendering its connective and peripheral parts as significant as its central elements. Merely to be exposed to it was (in theory) to disperse the stale, institutionalized consciousness with class-stratified society supposedly exuded like some kind of cognitive smog. Whether such anarchizing effects, hoped for by groups such as both Fluxus and the Situationists, really contributed to the changes in custom and morality seen in the West since the ‘60’s, is hard to say. Many consider the violent discontinuity of modern life to be rooted in the revolutionary disruptions of the 1960’s.

Though its secret impact is often acknowledged by artists, many art critics and art historians still can’t quite agree on its overall importance, perhaps due to the ephemeral, anti-commercial, and even immaterial nature of its artworks. But it drew heavily on non-western visual traditions. Art historian Richard Dorment has noted that it

refus[ed] to distinguish between high and popular art, designating as ‘art’ formal gestures, ritualized actions and a conscious aesthetic appreciation of the mundane. Members of Fluxus were musicians, artists, designers, dancers and poets---but what each individual did, played, made, or wrote was of relatively little consequence, since all were working together. It was fun to know someone associated with Fluxus, since communications with them, often by post, were apt to contain bits of collage, poetry or instructions to perform a series of absurd ritualistic acts.

And naturally enough, some of these rituals, such as LaMonte Young’s drone music, were of a slow and meditational duration, designed to inspire, if not actually provoke, the sudden illumination known in Zen as Satori. Such insights might also provide the way to appreciating how such experimental art and music managed, against all odds considering how subversively anti-market and anti-entertainment they were, to succeed in outlasting many more fleeting aspects of popular culture. Therefore, such art is actually real estate of the mind, so to speak. But as we clearly see in our examination of Buddhism in the context of the avant-garde, and avant-gardism in the context of Buddhist practice, there never really was a border in the first place. Only in our minds.

|

| Crow Dancer, Franz Kline, 1958, |

"There is no such thing as an empty space or an empty time. I have nothing to say / and I am saying it / and that is poetry / as I need it." – John Cage, Lecture on Nothing (1949).

Upon closer inspection it becomes utterly clear that a hidden avant-garde spirit had always been hiding in most Eastern cultures, dormant perhaps beneath reified traditions, but gestating nonetheless. This is especially the case if one believes, as I do, that Buddhism itself is already a radical departure from conventional linear thinking and contains a multitude of avant-garde attitudes towards being, behaviour and conduct, all of which can merge in an ideal manner with the fresh new ways of looking at all art and culture, not just abstraction. It does, however, find fertile inspirational ground in the realm of counterintuitive art associated with pure chance, multiple meanings and indeterminancy most identified with the experimental modes of the mid 20th-century era.

The real question, as I’ve intimated, is not so much whether Buddhism influenced the avant-garde, but whether Buddhism was an avant-garde modality already, two and a half millennia before Europe and America patted themselves on the back for ‘inventing’ abstract expressionism. It is now high time for a study of the intimate interplay between experimental artists of the West and experiental artists of the East, and the ways in which their interactions manifested a new hybrid form of self-expression based on selflessness. We might consider this an aerial overview of avant-garde artists who espouse, either overtly or covertly, an embrace of the active void principle in aesthetics.

This is a landscape which is best traversed from a very high altitude, in order to properly, or effectively, demonstrate and illustrate how all those fields crisscross and overlap with one another. From this aerial view, a look at and listen to the many avant-garde and Buddhist shared modalities becomes not only more accessible but downright essential. The Beats were the first sub-culture movement in America to fully embrace the central tenets of emptiness, transience and impermanence at the heart of all basic Buddhist principles, and both the writers and visual artists of the time used their media as vehicles to explore and share these mysterious ideas.

It’s clear that this growing interest in the East’s perceived spontaneous, unmediated experience had been simmering for some time in the West, especially in the capitals of the new and untried, even though many of its new anti-modernist notions were actually as old as the hills. This romantic concept of what the East represented was, for American artists, ostensibly a way to escape the grip of Western progress, and had begun to filter its way into America’s underground minds through the missionary zeal of the Beat Generation, the designers of Happenings, the New Left radicals, the West Coast poets, the jazz musicians, and anyone else tired of constrained Western rationalism. Of course, simple statements about inner peace, such as “the Way is no more than one’s everyday experience . . . when you begin to think you miss the point,” were also hugely attractive to the evolving counter-culture of the time.

Many of these historic contributions were uniquely focused on the interactions between the looseness of Beat culture and the formality of Zen culture, a paradoxical marriage to be sure: “Zen emphasizes art as a focus of everyday life and makes clear that there is no difference between the perceiver and perception. It sidesteps aesthetics through the act of immediacy and the inability to erase or second guess one’s moment of creation.” That sounds like a textbook definition of the tenets of abstract expressionism, and is further clarified by an understanding of how, who, where and when such transmission occurred.

The American Beat and Zen poet Gary Snyder expressed it even more bluntly in his interview during a film by Michael Goldberg, The Zen Life, a profile of his teacher D.T. Suzuki, when he mused about the cross-pollination of philosophy occurring from the most unlikely and unexpected of occurrences: “It took America dropping the Atomic bomb for the West to become interested in Zen.”

One ideal example of this direct transmission notion in the phenomenon of Buddhism and the avant-garde, which brings us from the middle of the 20th century to practically the mid-stages of the 21st, is the major influence of a Zen-adept artist we’ve already considered, the radical composer maverick John Cage, upon a contemporary abstract painter of huge importance in today’s art world, Gerhard Richter. This one example is a perfect vehicle for grasping the uncanny parallels between spiritual transmission from teacher to student and that brand of aesthetic transmission conducted from one artist to another in wide intergenerational modes.

During a memorable 1960 performance at a Fluxus Festival at New York’s New School for Social Research, the famed painter Richter watched in awe as Cage attached microphone to a pen and hooked the mic to an amplifier turned up to high volumes: “As Cage wrote with the pen, the audience heard the scratching of the nib across the paper surface. The amplified sound of the pen reverberated like thunder. Whatever Cage was writing was irrelevant. The pen spoke its own ragged, jaggedly authentic voice. Richter would have felt the intensity of raw sound unadulterated by any self-expression.”

Many years later, Cage saw an exhibition of Richet’s work and was taken by its resonant power. At neither event did the two artists ever meet or talk together, yet their works have since been conversing for decades. Critic Robert Storr has remarked on “this charge or current going back and forth” between them and their works. Richter has forever after been making what amounts to visual music, in which time, or empty duration rather, is frozen right there on the canvas. Storr likewise commented, “Artists perhaps understand one another best through their work—in which everything is revealed, a wordless transmission, even as everything is unspoken. What can be said? Yet the work, if it’s ground in zero, communicates what’s needed.” Amen.

That observation, which suggests that the inner life of artists is actually communal, is itself, of course, pure Zen of the highest order, and it manages to convey the phenomenal transmission of Buddhism through the avant-garde’s ongoing creation of embodied meanings in multiple media, each of which, whether poetry, music, painting, dance, sculpture or craft, somehow approaches the possibility of communicating the ineffable. It also reminds us all that in consciousness there is East or West, or any other direction really, and it compels us to carefully modify that famous lyric from an oft-quoted Rudyard Kipling poem: East is East and West is West, and always the twain shall meet. With Buddhist inspiration, the avant-garde melted that twain.

– Donald Brackett is a Vancouver-based popular culture journalist and curator who writes about music, art and films. He has been the Executive Director of both the Professional Art Dealers Association of Canada and The Ontario Association of Art Galleries. He is the author of the recent book Back to Black: Amy Winehouse’s Only Masterpiece (Backbeat Books, 2016). In addition to numerous essays, articles and radio broadcasts, he is also the author of two books on creative collaboration in pop music: Fleetwood Mac: 40 Years of Creative Chaos, 2007, and Dark Mirror: The Pathology of the Singer-Songwriter, 2008, as well as the biographies Long Slow Train: The Soul Music of Sharon Jones and The Dap-Kings, 2018, and Tumult!: The Incredible Life and Music of Tina Turner, 2020. His latest work in progress is a new book on the life and art of the enigmatic Yoko Ono, due out in early 2022.

No comments:

Post a Comment