Independent reviews of television, movies, books, music, theatre, dance, culture, and the arts.

Monday, December 5, 2011

Jazz Babies: Cotton Club Parade

Tuesday, February 8, 2022

The Tap Dance Kid: Which Show Are We In?

|

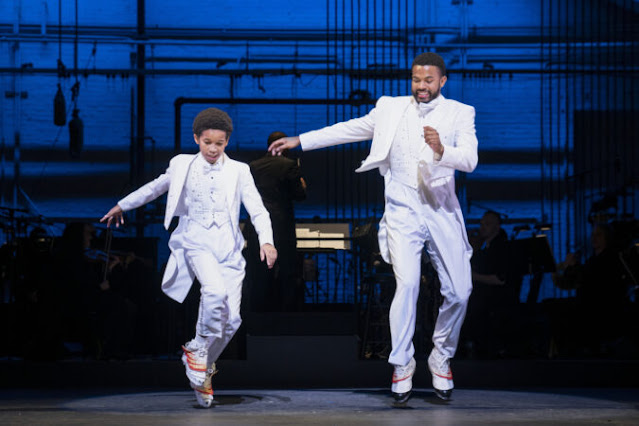

| Alexander Bello and Trevor Jackson in The Tap Dance Kid. (Photo: Joan Marcus) |

The return of the Encores! series to City Center over the weekend after two years in hiatus was eagerly anticipated, but the occasion – a revival of the 1983 musical The Tap Dance Kid – turned out to be dispiriting. To start with, the show, which I missed the first time out, isn’t very good. Charles Blackwell’s book (based on a novel by Louise Fitzhugh – of Harriet the Spy fame – called Nobody’s Family Is Going to Change) is a retread of the antique melodramatic plot about the boy who has to fight his stiff-backed father’s bias against show business to follow in his dancer-choreographer uncle’s footsteps and dance his heart out on the stage. Here he’s a ten-year-old Black kid from the Buffalo suburbs named Willie (played by the personable Alexander Bello) whose mother, Ginnie (Adrienne Walker), danced with her kid brother Dipsey (Trevor Jackson) and their gifted father when they were children. Ginnie raised Dipsey in cheap hotels on the road and took care of him when Daddy Bates went on benders. Then she married William (Joshua Henry), an ambitious lawyer who promised her a safe, respectable life. He delivered, but his vision of family life and of what bringing glory to the race is highly restrictive. He’s suiting up his son, who is bored in school but deliriously happy when he’s taking tap lessons from his uncle, for a career in law, while his teenage daughter Emma (Shahadi Wright Joseph), a bright young woman who covets that career for herself, can do nothing to gain his approval. He’s not interested in Emma; she’s only a girl. And he bullies his wife, silencing her objections and making jokes about the troublesome women in this family. When Willie’s bad grades provoke his father into taking away his tap shoes and banning Dipsey from his home, the boy runs away to his uncle, who’s rehearsing a musical downtown that he hopes will be his ticket to Broadway. What it needs to succeed, in case you haven’t guessed, is a talented tap dance kid.

Monday, April 10, 2023

Musical Revivals I: Funny Girl and Dancin’

.jpg) |

| Lea Michele in Funny Girl. (Photo: Matthew Murphy) |

The Broadway revival of Funny Girl is a hit, but its path has been slippery. Michael Mayer’s production started in London, opening at the Meunier Chocolate Factory in 2016 with Sheridan Smith. But when it transferred to the Savoy Theatre in the West End, Smith dropped out due to stress and exhaustion and was replaced by her understudy, Natasha Barnes. That’s when I caught it, and without a luminous Fanny Brice to anchor the musical that made Barbra Streisand famous – and vice-versa – it wasn’t much. The modesty of the staging and designs was just over the line from looking seedy, and since the cast was so small, the supporting players as well as the chorus had to join in the dances that bridged – somewhat desperately – the many scenes, Funny Girl being a representative of the last successful decade of large-scale Broadway musicals.

Monday, December 16, 2013

Heart and Soul: Camelot & After Midnight

Monday, May 28, 2012

Back to Coolidge: Nice Work If You Can Get It and Gentlemen Prefer Blondes

|

| Matthew Broderick and the Cast of Nice Work If You Can Get It |

With the obvious exception of George and Ira Gershwin, no one involved with the new Broadway musical Nice Work If You Can Get It is at his or her best: not the director-choreographer, Kathleen Marshall (also represented currently on Broadway by her irresistible production of Cole Porter’s Anything Goes), or the two stars, Matthew Broderick and Kelli O’Hara, or the scenic designer, Derek McLane or the costume designer, Martin Pakledinaz. Joe DiPietro’s book is a limp reworking of the plot of the Gershwins’ 1926 hit musical Oh, Kay! (the original was the work of those skillful musical-comedy wordsmiths, Guy Bolton and P.G. Wodehouse) about the romance of a playboy and a bootlegger whose hooch is stashed in the cellar of his Long Island mansion. It would have made sense for Marshall to stage a revival of Oh, Kay!, which still has a lot of charm and a delectable score. (You can hear the score complete, impeccably restored by Tommy Krasker, on a 1994 Nonesuch recording with Dawn Upshaw as Kay.) Nice Work is a jukebox musical with twenty-one Gershwin tunes shoehorned in, many of them randomly. Often musicals in the pre-Show Boat days (Oh, Kay! was one of the last, opening just thirteen months earlier) and even afterwards were just vehicles for songs and performers, but as disposable as the dramatic situations may have been, the songs generally fit them. At least a third of the song cues in Nice Work are about as convincing as the ones in Mamma Mia!: Billie (O’Hara), the renamed heroine, may be feisty but she’s not the kind of girl who would demand of a would-be lover, “Treat Me Rough.” And why, exactly, is she singing “Hangin’ Around with You” while (masquerading as a domestic) she serves dinner to Jimmy (Broderick) and his house guests?