|

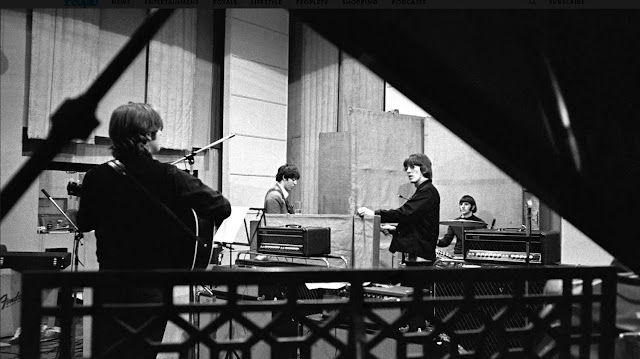

| The Beatles in Abbey Road Studios during filming of the "Paperback Writer" and "Rain" promo films. (Photo: Apple Corps) |

A pitfall of trying to understand history is the narrative fallacy. It means deciding, often on scanty evidence and against opposite indications, that things happened a certain way for certain reasons, and then revising every conclusion to fit that faulty or incomplete picture. An example is the still-common characterization of The Beatles’ 1968 White Album as a study in dissolution because a) we know the group were having difficulties at the time, and b) John Lennon decided to describe it that way: “It’s like if you took each track off it and made it all mine and all George’s . . . It was just me and a backing group, Paul and a backing group.” There’s no reason not to hear the 1966 Revolver likewise, as a collection of solipsistic fragments. But we never have, because the dissolution narrative doesn’t commence until later—after Brian Epstein dies, Magical Mystery Tour bombs, and Yoko arrives. In fact, Revolver has long been held up as the summa of the group’s creative unity, despite being as diverse and divergent as the White Album.

The moral: always question the narrative you’ve inherited. Another moral is that there are different kinds of unity—a kind you hear, and a kind you feel. The first manifests in surfaces, where the second tends to lie deeper, in the constitution of a thing. Consistency of production and design gives Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band a hearable unity, a smooth skin. Revolver, like the White Album, has a variable surface—spiky and metallic here, burnished and oaken there—yet it feels unified in every cell. The bonding agent is the willingness of each member to give whatever he has to another’s self-expression in a series of powerfully subjective moments.

These rambling thoughts are inspired by a weekend’s immersion in the new Revolver deluxe box set. Excepting 2020, lost to the lockdown, each of the last six years has seen an elaborate fiftieth-anniversary release constructed around a late-stage Beatles album. The first was devoted to Sgt. Pepper; the White Album and Abbey Road followed. The Let It Be box appeared a year off-schedule, but in synch with the acclaimed Get Back documentary. Each package has been executed with love, care, and discrimination; each has enlarged and even reshaped one’s relationship to the original work. (It took the Abbey Road box to make this doubter fully appreciate that record’s warmth and richness.) The latest release continues this series of marvels. Revolver in its deluxe form contains a new stereo mix crafted by Giles Martin (son of Beatles producer George Martin) and Sam Okell, and a transcription, direct from master tapes, of the original mono mix. An extended-play disc contains both new stereo and original mono mixes of “Paperback Writer” and “Rain,” songs recorded during the Revolver sessions for advance release as a single. There’s an accompanying book, and two discs’ worth of session outtakes in a glossy jacket reproducing the original cover concept (a concentricity of Beatle faces, designed by Robert Freeman).

Some fans are complaining about the absence of a Blu-ray component, or a shortage of outtakes. Other pecks and nits will surely be posted to the digital corkboards of virtual communities. But really, what can we say in response to this box, or its predecessors, but “Thank you”? Second-generation Beatle fans in particular—we who were a little too young to have seen them in real life and real time; who once found life-giving treasure in crappy mail-order cassettes containing fuzzy offline recordings of cheap vinyl bootlegs; to whom every scrap of Beatle video was not simply the nightly news but a transmission from another, happier world—could never have dreamed of living in a future this rich in discovery and rediscovery.

The familiar, finished songs of Revolver are not diminished by proximity to their own rough drafts and remakes. If anything, the album’s impact, its exotic swirl of riffs and atmospheres, gains in intensity. The sessions begin with that mind-altering concoction, “Tomorrow Never Knows.” A dense and droning first version, kicked into gear by Ringo’s late arrival and transfixing all the way through, is discarded for a remake in which an electronically fried Lennon dispatches mind mantras from a beach at the edge of the universe. The sessions end with the Möbius-strip guitars and uncoiling images of “She Said She Said,” a song remarkable for its decision (and it feels like the song’s decision, not the band’s) not to step back from itself for a moment, not to pause for a solo or a breath of the conventional. In between that leaping start and that heedless finish, The Beatles repeatedly find the exact detail that will give each song its flavor of unreality, or of reality—whether it be the sour, twitchy piano note of “I Want to Tell You”; the 12-string guitar piercing the velvet bubble of “Here, There and Everywhere”; or the backwards solo of “I’m Only Sleeping,” a sound which undulates and elongates like a conjured spirit, before vanishing as if snatched away by unseen hands.

As a repository of outtakes, Revolver doesn’t have the depth or variety of Pepper or The White Album. The Beatles were under intense time pressures in early 1966 (they finished the last Revolver song just two days before starting a world tour), and so lacked the luxury, later fully exploited, of letting songs develop over a multiplicity of takes and approaches. This leaves far less material for compilers to draw on—fewer demos, fewer dialogues, and, except in a couple of cases, fewer radical transformations in the shaping of arrangements. But all that granted, the outtakes are frequently fantastic. Almost none has ever been heard outside of EMI Studios; those that have, either on bootlegs or on the 1996 Anthology 2 compilation, are newly augmented with studio chatter, and most are played to a full stop rather than faded out.

Heard at original speed, the “Rain” backing track seems almost Chipmunk fast, accustomed as we are to the narcotic lassitude of the final version. The speed only renders Ringo’s drumming and Paul’s bass more inexplicable: they play as if unconscious—or hyperconscious, you’re not certain which. (Ringo astonishes throughout, particularly on the “Paperback Writer” and “She Said She Said” takes.) For an acoustic demo of “Yellow Submarine,” whose final form fused Lennon verses with a McCartney chorus, John sings his bit alone; plain and melancholy, it looks ahead to the Liverpool nostalgia of “Strawberry Fields” and “Penny Lane.” Take 5 of “And Your Bird Can Sing” shows some interesting variations in vocal and riff, but at this point the song drags instead of flies. (The released version, two minutes of pop perfection, lay five takes into the future.) Aside from “Tomorrow,” “Got to Get You into My Life” undergoes the most startling change—from a sensual, organ- and harmony-driven flirtation (both parody and prediction of where The Beach Boys were heading) to a piece of hot rock whose fuzz guitar may have been influenced by “Think,” from The Rolling Stones’ just-released Aftermath (a studio shot shows Paul eyeballing that album). Both earlier versions are dynamite—but the addition of horns, showcased here in a backing track, sets the song ablaze.

|

| Photo: Apple Corps |

The new stereo mix has a backstory that explains why the Revolver box isn’t keyed to an original release date. It was long assumed that the pre-Pepper albums couldn't be remixed due to the limitations of their making. Typically, The Beatles recorded a song’s basic backing on four-track tape, adding one or two overdubs before copying the result to another tape in a “reduction mix,” thereby creating space for further overdubs. This left multiple musical elements crowded onto single tracks, making them impossible to separate for remixing. But during the creation of the Get Back documentary, Peter Jackson’s audio team, working with monophonic tapes, used Artificial Intelligence to separate previously fused strands of sound—Beatle voices from background voices, important dialogue from extraneous ambience. Someone realized that the same capability could be applied to the Revolver tapes, and here we are. (Presumably this “de-mixing” process can be applied to the remaining albums as well.) Whether due to the limits of AI or to qualities inherent in the original tapes, this Revolver doesn’t feel quite as wowing as Giles Martin’s other anniversary remixes. Nor does it necessarily have to. As Martin writes in a forward note, “there’s nothing too extreme here . . . I never want anyone to hear the mixes.” Even so, this version is far more robust, in every way fuller than the tin-can stereo that has predominated at least since the Beatles first migrated to CD. Subtleties both accidental and intentional are brought up a level; the bass has more beef, the guitars more bite; and you get a better sense of how the harmonies are constructed. Each ear will make its own discoveries.

The accompanying book combines a substantial text with tasteful design, handwritten lyrics with reproduced tape boxes and session chits, Robert Freeman’s Abbey Road photographs with publicity shots taken by Robert Whitaker at the March 1966 session that produced the “butcher cover.” Several pages are given to Klaus Voormann’s graphic illustration (excerpted from a newly published, limited-edition work) of how he came to create the Aubrey Beardsleyesque cover collage that supplanted the Freeman kaleidoscope. Kevin Howlett, reliably meticulous annotator of Beatle reissues, contributes essays on Revolver’s genesis and reception, as well as thorough notes on each track. A certain kind of fan will love the deep data on EMI recording techniques, circa 1966, including tales of the Fairchild 660 limiter, Automatic Transient Overload Control, and innovations in bass amplification. Among the historical nuggets are George Harrison’s fixation, relevant to “Taxman,” on England’s order of F-111 fighters from the U.S. (later canceled, to the chagrin of Secretary of State Dean Rusk); John Lennon scribbling lyrics on an unpaid bill for the radiophone in his Rolls Royce; and hints, reverse-decoded in part from a surreptitiously recorded exchange in the Get Back documentary, of a minor spat which may have prompted a McCartney walkout during the sessions.

Also in the book is a personal appreciation of Revolver by Questlove, co-founder of The Roots and director of last year’s marvelous Summer of Soul, about the 1969 Harlem Cultural Festival. Resistant to The Beatles as a child because the vintage rainbow label on their US Capitol albums “reeked of old people,” he came to the group gradually, through solo hits on radio and cultural effluvia like the Beatlemania stage show. Later, taking a chance on Pepper, he discovered how many of the album’s traces were submerged in his musical unconscious; within a few years, he would own all of their albums. Questlove tells a great story of DJing “in the UK in the dead of winter”: it’s late, he’s tired and wants to pack up, so he puts on “Love You To,” hoping its esoteric timing and morbid vibe will disperse the crowd. But it has the opposite effect: Harrison’s sitar intro—the sound of mercury shimmering in slow motion—creates instant excitement, and the sudden break into pounding, undeniable rhythm ignites another hour and a half of dancing.

Pepper may have been Questlove’s first Beatles album, but Revolver became his favorite. The fact is, no fan loves the two equally, just as none of us places the White Album and Abbey Road—wiser, more sprawling realizations of the earlier albums’ respective approaches—on the same level. Everyone falls toward one or the other, and what I find interesting is that each fan’s preference will probably depend on whether they are drawn more to the conscious or the unconscious in human affairs. Where Pepper is shaped as a series of public performances, spotlight turns before a “live” audience, Revolver is more like a series of shadow plays occurring in private rooms. Pepper happens in the clarifying gleam of an ideal stage, with well-rehearsed moves beautifully executed for direct response. Revolver is a trip up and down a dark hallway, seven doors on one side and seven on the other, all ajar and accessible, with players and auditors sharing the same hypnagogic state—that “twilight zone” where Paul McCartney has often said he first saw the yellow submarine. Pepper is a show put on for our entertainment; Revolver’s little dramas will unfold whether we’re there or not.

The Beatles’ late albums are inkblots: our responses to them reveal something about our approach to art in all its forms, to other people, even to life. Or maybe they don’t. (Always question the narrative.) But what seems evident from any perspective is that Revolver is extraordinary not only for the diversity but also for the collectivity of its dreaming—the ease and grace with which three Beatles, finding themselves in the fourth Beatle’s mindscape, take up instruments and find voices to bring it forward. That is my narrative of Revolver, at least for today. You’re bound to create your own.

– Devin McKinney is the author of Magic Circles: The Beatles in Dream and History (2003), The Man Who Saw a Ghost: The Life and Work of Henry Fonda (2012), and Jesusmania! The Bootleg Superstar of Gettysburg College (2016). Formerly a music columnist (The American Prospect), blogger (Hey Dullblog), and TV writer (The Food Network), he has appeared in numerous publications and contributes regularly to Critics At Large and the pop culture site HiLobrow. He is employed as an archivist at Gettysburg College in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, where he lives with his wife and their three cats. His website is devinmckinney.com.

Hi Devin, Donald Brackett here. That's an excellent angle of approach, and one from the appropriate altitude too. Thanks for this piece.

ReplyDeleteInsightful writing, Mr McKinney! Interested to hear your thoughts on the Lennon Yellow Submarine demo, for me it was the most revelatory part of the box set. Also Magic Circles is one of the best books about The Beatles ever published. 👍

ReplyDelete