|

| Guillaume Côté in Grand Mirage. (Photo: Karolina Kuras.) |

Independent reviews of television, movies, books, music, theatre, dance, culture, and the arts.

Friday, June 6, 2025

Guillaume Côté’s Adieu: A Daring Farewell at the National Ballet of Canada

Tuesday, May 20, 2025

The Extraordinary Adam Guettel: The Light in the Piazza at The Huntington and Floyd Collins on Broadway

|

| Emily Skinner in The Huntington Theatre's The Light in the Piazza. (Photo: Julieta Cervantes.) |

The new Huntington Theatre mounting of The Light in the Piazza is the fourth production I’ve seen of this show, and except for Bartlett Sher’s spectacular original staging, at Lincoln Center in 2005, it’s the best. I think that Piazza, with its first-rate Craig Lucas book derived from Elizabeth Spencer’s 1960 novel and its soaring impressionistic score by Adam Guettel, is the greatest musical written in the twenty-first century. (Yes, I love Hamilton.) It’s an unconventional romantic musical in which the leap of faith made by the wife of a North Carolina tobacco executive named Margaret Johnson, who brings her daughter Clara to Florence on vacation in 1953, is a symbol for all of our attempts to find happiness in love, even though we know that the effort is reckless because as often as not it ends in shambles. One of the elements that make the play unusual is that though the lovers are Clara and a young Florentine named Fabrizio Naccarelli, the son of a shopkeeper, who fall in love at first sight. Margaret is the protagonist, and it’s finally she who has to overcome personal obstacles, not her daughter. She has been Clara’s protector since, at twelve, the girl was kicked in the head by a pony, apparently halting her emotional development. So when she and Fabrizio become entranced with each other, Margaret – encouraged via long distance by her husband Roy back home in Winston-Salem – attempts to stop it before the humiliating moment when the Naccarellis figure out something is wrong. But no one in the Naccarelli family is put off by Clara’s childlike nature, or even by her explosion when Fabrizio’s flirtatious sister-in-law, Franca, gets too close to him at a family get-together. The Naccarellis find her refreshingly old-fashioned; even Franca, whose attention-getting behavior is a response to her husband’s sexual duplicitousness, defends her; she thinks that Clara is right to fight for her man she loves and even wishes she had done so. Margaret has to confront the fact that the greater block to her approving Clara’s union with Fabrizio is the fact that her own marriage has been a disappointment, that she long ago ceased to believe in love.

Sunday, February 16, 2025

Intoxicating: People, Places and Things at Coal Mine Theatre

|

| Kwaku Okyere, Louise Lambert, Sarah Murphy-Dyson and Nickeshia Garrick in People, Places and Things (Photo: Elana Emer) |

Duncan Macmillan’s People, Places and Things has landed at Toronto’s Coal Mine Theatre in a production that is as intimate as it is harrowing. Directed by Diana Bentley, this Canadian English-language debut transforms the celebrated 2015 play into an immersive experience, leveraging the theatre’s compact, square stage to pull the audience into Emma’s chaotic journey through addiction and recovery.

Thursday, January 16, 2025

Coming of Age as an Apologue – and the Reverse

|

| Elliott Heffernan and Saiorse Ronan in Steve McQueen's Blitz. (Photo: Parisa Taghizadeh/Apple TV+.) |

Steve McQueen’s film Blitz, set in September 1940, in the early days of Hitler’s incessant bombing of London, is an obvious labor of love. It takes place over just a couple of days, during which Rita (Saiorse Ronan), an armaments factory worker, puts her nine-year-old son George (Elliott Heffernan), on a train bound for the countryside with other children but he jumps out and tries to make his way back to Stepney, the working-class neighborhood where he lives with Rita and her father (Paul Weller); he never knew his father, who is African and was deported unjustly after a street fight. Production designer Adam Stockhausen’s recreations of the period are gorgeous, as is the cinematography by Yorick Le Soux, the favorite collaborator of the French director Olivier Assayas. The editing by Peter Sciberras is masterful: it actualizes McQueen’s remarkable sense of rhythm, which was showcased in his Small Axe series and especially in Lovers Rock. The film is propelled forward, moving back and forth between Rita and her wayward boy with remarkable fluidity and from one London location to another so that the continuity is simultaneously whole-cloth and fragmented. It contains a number of beautifully constructed setpieces that rank with the finest work that has been done with this period in film. And along the way McQueen takes care to pay homage to some of its predecessors: Hope and Glory, Empire of the Sun, Saving Private Ryan, Atonement. (There’s also a subplot out of Oliver Twist and a speech in an underground shelter by a left-wing character, played by Leigh Gill, who seems to have been inspired by Agate in Clifford Odets’s Waiting for Lefty.)

Sunday, November 17, 2024

Liquid Moonlight: The National Ballet of Canada’s 2024 Winter Season

|

| Christopher Gerty and Hannah Galway in Silent Screen. (Photo: Bruce Zinger) |

Last Saturday night, the National Ballet of Canada launched its winter season at Toronto’s Four Seasons Centre with a triple bill featuring works new to the company. Running until November 16, the two-hour program included Sol León and Paul Lightfoot’s evocative Silent Screen, Frederick Ashton’s sparkling Rhapsody, and Guillaume Côté’s introspective Body of Work. Côté’s solo piece expressed his personal connection to dance as he prepares for retirement at the end of the 2024/25 season.

Tuesday, July 16, 2024

Standing at the Sky’s Edge: Working-Class Heroes

The cast of Standing at the Sky's Edge in the West End. (Photo: Brinkhoff-Moegenburg)

Standing at the Sky’s Edge is playing to enthusiastic audiences in the West End after transferring from the National’s Olivier Theatre. Its original home was the Crucible Theatre in Sheffield, where it opened in 2019 and again in 2022, and Sheffield is its setting – specifically Park Hill, a high-rise public housing project built in 1959 to replace the slum housing that had dominated the area since the 1920s. Standing at the Sky’s Edge is a Brechtian jukebox musical that chronicles the history of Park Hill. The music is by singer-songwriter Richard Hawley, a son of Sheffield who played in several Britpop bands before going solo in the early days of the millennium. Hawley isn’t well known on this side of the Atlantic, but a friend turned me onto his music after he released his third solo album, Coles Corner. He’s a balladeer, a working-class romantic with a throbbing, plaintive voice and a distinctive stripped-down lyricism. His music is the beating heart of the production and the musical director, Alex Beetschen, and the beautiful, full-throated voices of the ensemble bring out its latent exuberance.

Monday, June 3, 2024

London Tide: Dickens and Brecht

|

| The cast of London Tide at the National Theatre, London. (Photo: Marc Brenner) |

As I think is often the case with the iconic nineteenth-century realists, Charles Dickens’s style has never fitted snugly into the official definition of realism. It’s realism embellished, realism plus. In his characters, especially the most memorable ones, the qualities that delineate them, like Miss Havisham’s desire for vengeance against the male sex in Great Expectations and Mr. Micawber’s eternal optimism in David Copperfield, are so exaggerated that the characters become metaphors for those qualities. Dickens’s genius for inventing imaginative visual symbols that sit alongside the characters – for Miss Havisham, the stale, mice-ridden wedding cake and the clock stopped at the moment when her intended groom abandoned her at the altar – enhances the process, lending the stories the aura of enchantment, which goes along with the author’s predilection for moral fables. What situates him in the realm of realism is a combination of his abundant love of detail and his psychological insight, particularly in the passages that elaborate the experience of a feeling or the nature of a behavior. Those are the moments in his novels when the abstract is transformed into the specific, which is the way realism works. That transformation is the midpoint between abstraction and universality: if the writer has rendered the general as an image so precise and layered that we can recognize it from our own experience, then we can see straight through its replication of real life to a profound truth. If you try to boil down Dickens’s approach to simple caricature, you can make him sound like it’s linked to what Brecht did later in his plays, but it’s the opposite – he’s not using exaggeration to distance his readers but to draw us in.

This distinction occurred to me while I was watching Ian Rickson’s Brechtian production for the National Theatre of London Tide, which Ben Power has adapted from Dickens’s Our Mutual Friend. Our Mutual Friend is one of the writer’s more obscure works and one of the most fascinating. It showcases common vices that take up residence in our blood: greed, jealousy, ambition and pride. We struggle against them, unless we succumb to them and become their agents, as do a number of the novel’s characters. It’s also about the corrupt values of an entrenched class society that reinforces those vices. When it appears that John Harmon, the estranged only son of a London rubbish magnate, has been drowned in the Thames River, the fortune he would have inherited goes instead to the millionaire’s loyal servants, the Boffins. They are generous enough to invite the heir’s intended bride, Bella Wilfer, who comes from a poor family, to move in with them and share their wealth. She is happy to do so; she never met her fiancé – their marriage was arranged by the millionaire – but now she feels abruptly disenfranchised, and she loves the idea of being rich. The complication is that Harmon isn’t really dead; the corpse that has turned up in the tide is of another young man bearing Harmon’s identifying papers. Liberated from the manipulations of an unkind father, Harmon takes another name, John Rokesmith, then secures the post of secretary to the Boffins so he can observe Bella. And he falls in love with her. So he sets a test to see whether she can get past her attraction to money if she sees at first hand how damaging it can be.

Tuesday, November 21, 2023

Feeling Her Pain: Emma Bovary at the National Ballet of Canada

|

| Hannah Galway and Siphesihle November in Emma Bovary. (Photo: Karolina Kuras/Courtesy of The National Ballet of Canada) |

Emma Bovary ran at Toronto’s Four Season’s Centre from November 11-18.

In the promo video the National Ballet of Canada put out in advance of the world premiere of Emma Bovary, choreographer Helen Pickett says that her intention was to get the audience to understand what the titular character – one of the greatest female creations in all of literature – is feeling. That undersells it.

A triumph of dance-theatre where every gesture is loaded with narrative meaning, Emma Bovary evokes a visceral response in the audience. Much like Gustave Flaubert’s original mid-19th-century realist novel, the experience is vividly complex. We are riveted, repulsed, seduced, astonished, amused, horrified and ultimately sympathetic. Gratification is also part of the emotional mix. Together with her collaborator, the English theatre and opera director James Bonas, the California-born Pickett – a former Ballet Frankfurt dancer who has choreographed more than 60 works – has created an ultra-physical narrative ballet so potent it grabs you at your core.

Monday, October 16, 2023

“The Great Gambon”: A Tribute to Michael Gambon

|

| Michael Gambon as the ailing writer in The Singing Detective (1986). |

Michael Gambon, the towering English actor who died on September 27 at the age of eighty-two, had such a distinctive, jowly appearance that if he’d been born American and looked for work in Hollywood he certainly would have been typecast in gangster roles. He was lumpy and broad-shouldered and he had the long, rectangular face of a weary pugilist, with tiny eyes peeking out from beneath heavy, outsize lids and from above cheeks like thick pillows. Yet he had universes in him. He was born in Ireland but his family moved to London and then to Kent, where he apprenticed as a toolmaker. He caught the acting bug when, laboring on set crew for an amateur dramatic society, he was asked to play some small roles. Eventually he joined the Gate Theatre in Dublin under Micheal MacLiammoir and Hilton Edwards and the Royal National Theater under Laurence Olivier, who was his role model – Olivier, whose physical and vocal transformations were legend, who could bury himself in a character. No one who looked like Gambon could help being recognized in part after part, yet his range was as staggering as that of any British performer of his astonishing generation, and his metamorphoses could be so miraculous that they seemed to trick the eye. In the role with which most moviegoers identify him, the Hogwarts schoolmaster Albus Dumbledore in the Harry Potter series, which he took over in Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban in 2004 following the death of Richard Harris, he has the paradoxical look of a giant elf. Harris’s Dumbledore is other-worldly and wrapped in wonder; Gambon’s is Zen and self-amused – Yoda reborn as a lordly English eccentric whose white hair and beard complete him.

Monday, June 19, 2023

Shakespeare in London

|

| The closing image of The Comedy of Errors at the Globe. (Photo: Marc Brenner) |

One of the consequences of Covid and its attendant economic challenges for London theatre is the shortage of classical English productions this summer – even, and most glaringly, Shakespeare. This is the only time I’ve ever been in London at this time of year when the National Theatre isn’t mounting a single play by Shakespeare. All I’ve managed to see are The Comedy of Errors (his first comedy) at Shakespeare’s Globe and Romeo and Juliet (his earliest tragedy) at the Almeida.

Tuesday, October 4, 2022

Coming Around Again

David Adkins, Corinna May, Tim Jones and Kate Goble in Seascape.

This article includes reviews of Seascape, Persuasion, Mrs. Harris Goes to Paris and Sing Street.

Edward Albee’s Seascape first appeared on Broadway in 1975, in a production he directed that featured Barry Nelson, Deborah Kerr, Frank Langella and Maureen Anderman. Its run was short – a couple of months – but it won Albee the second of his three Pulitzer Prizes. (The others were for A Delicate Balance and Three Tall Women.) Though it’s a marvelous work, but it seldom comes up for revival, presumably because it’s such an oddity. It’s about a meeting between a middle-aged couple, marking retirement with a beachside vacation, and a pair of lizards, also a couple, who have come up from the sea; Albee, taking the special poetic license reserved for absurdists, has conveniently allowed the lizards to converse in English. With its taste for revisiting plays, mostly American, that have fallen into obscurity, Berkshire Theatre Group has just opened Seascape at its Unicorn Theatre in Stockbridge. This is only the second time I’ve seen it performed. Mark Lamos staged a dazzling production in 2002 with a flawless cast – George Grizzard, Pamela Payton-Wright, David Patrick Kelly and Annalee Jeffries; I can still remember the costumes Constance Hoffman designed for the lizards. Lamos remounted it at Lincoln Center in 2005 with Grizzard, Frances Sternhagen, Frederick Weller and Elizabeth Marvel.

Friday, March 11, 2022

Last Stop: Ballerina Sonia Rodriguez’s Farewell Performance in A Streetcar Named Desire

|

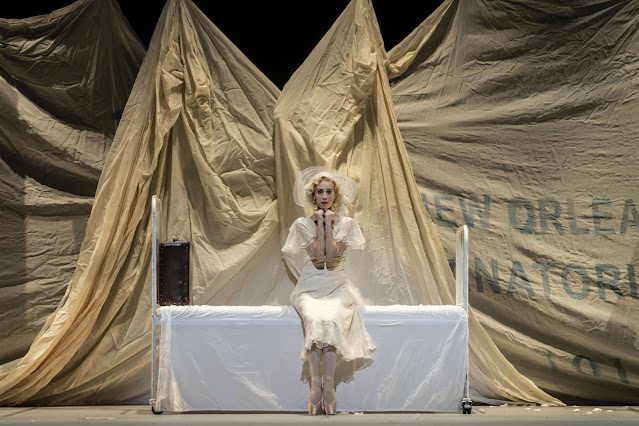

| Sonia Rodriguez as Blanche DuBois in A Streetcar Named Desire. (Photo: Johan Persson) |

Blanche DuBois, one of the most memorable female characters born of the theatre, is a hot mess of narcissism, nymphomania and other neuroses wrapped in white satin. A nervous breakdown just waiting to happen. The vaporous southern belle at the centre of John Neumeier’s ballet version of Tennessee Williams’s A Streetcar Named Desire requires a seasoned dancer who can peel back the layers to expose the fragility behind the tragedy of her fall. Sonia Rodriguez is that dancer.

Born in Canada, raised in Spain and trained in Monaco, the National Ballet of Canada principal is one of the country’s greatest dancer-actresses. She doesn’t just perform a part; she inhabits it, bringing it fully, palpably, to life. That’s her legacy, what she will be remembered for after leaving Canada’s largest ballet company following an illustrious 32-year career.

Thursday, December 9, 2021

Kathleen Rea: A Life in Motion

|

| Kathleen Rea in Five Angels on the Steps. (Photo: David Hou) |

Toronto indie dancer Kathleen Rea has put her life – the good bits and the not-so-good – in a dance created for her by friend and choreographer Newton Moraes. He’s credited as the choreographer. But Five Angels on the Steps, as this visceral and enigmatic solo is named, is so rooted in the performer’s own autobiography that it might be fair to label it more of a collaborative effort. It’s one woman’s personal journey rendered as a dance.

Tuesday, November 16, 2021

Raising the Curtain: The National Ballet of Canada Returns from Lockdown

|

| Artists of the Ballet in Angels ’ Atlas. (Photo: Johan Persson, Courtesy of The National Ballet of Canada) |

Excitement surrounding the return of the National Ballet of Canada to the Toronto stage, following 18 months of pandemic-imposed lockdowns, swelled as soon as the doors reopened at the Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts on Thursday night. “Welcome Back,” words writ large on the stage curtain, greeted the fully masked members of the audience as soon as they stepped into the theatre. The mood became immediately celebratory, jubilant, even festive, as if at any moment confetti would fall from the ceiling along with balloons.

Wednesday, October 6, 2021

The Right Touch: Guillaume Côté’s Immersive Dance Thrills the Senses

|

| Natasha Poon Woo and Larkin Miller in Touch. (Photo: Dahlia Katz) |

Physical contact – what we all once took for granted – has become a precious commodity in the pandemic. Social distancing, lockdowns and the wearing of masks have frustrated a basic need for human contact, compelling choreographer Guillaume Côté, a long-time National Ballet of Canada principal dancer, to delve deep into what it means to form a human bond. Touch, whose world premiere took place last week (and which will run until November 7) at what is left of the Toronto Star’s former printing press at One Yonge Street, explores the powerful dynamics arising from a close encounter between two people. But it’s much more than that. Billed as an immersive dance show, Touch harnesses laser mapping, light art technology and video integration to create an all-enveloping 3D-world where the quest for forging connections is not just a theme. It’s a stunning achievement.

Monday, May 10, 2021

Detective Story: C.B. Strike

|

| Holliday Grainger and Tom Burke in C.B. Strike. |

I fell for J.K. Rowling’s Cormoran Strike detective novels at the beginning of the series, The Cuckoo’s Calling, which she published in 2013. (She uses a nom de plume for these books, Robert Galbraith, but the beans were spilled after the first one was published.) As fans of the Harry Potter books might have expected, they’re intricately plotted, with wide-ranging, sharply drawn characters, and you wrap yourself up in them; once I start one I have to stave off the impulse to do absolutely nothing else until it’s done but turn the pages. She’s written five; the latest, Troubled Blood, came out last September. Her heroes, Strike and Robin Ellacott, run a successful London detective agency, though she starts, in The Cuckoo’s Calling, as a temp who gets a gig at Strike’s ragtaggle business. In the course of solving the crime, the killing of a famous model that the cops have dismissed as a suicide, both Strike and Robin herself discover her gift for investigation; and by the end of the novel he’s agreed to make her his partner.

Monday, February 15, 2021

“Oh, earth, you’re too wonderful for anyone to realize you”: Our Town and Another Day’s Begun

|

| Eric Stoltz and Penelope Ann Miller in Gregory Mosher's production of Our Town, 1989. |

I’ve been living with Our Town for more than half a century, so I was startled to discover, in the interviews Howard Sherman conducted with (mostly) actors and directors for his new book Another Day’s Begun: Thornton Wilder’s Our Town in the 21st Century, that so many theatre people were unfamiliar with the play when they signed on to participate in contemporary productions of it. I encountered Our Town in a literature class during my senior year of high school, and I recall vividly sitting in the front row, rapt, as my teacher read the third act out loud – and struggling, probably pathetically, to hide my tears as Emily, who has just died in childbirth, returns to relive her twelfth birthday but, overcome with the anguish of seeing her precious past from the perspective of one who knows the future, begs the Stage Manager to take her back to her grave on the hill. I fell completely in love with the play – and with Thornton Wilder, who had recently published his penultimate novel, The Eighth Day, which I subsequently devoured. (I reread The Eighth Day a couple of years ago; it really is the masterpiece I took it for at seventeen.) Wilder won the National Book Award for that book, four decades after he’d taken the Pulitzer Prize for his second book, The Bridge of San Luis Rey. He also won Pulitzers for Our Town and for The Skin of Our Teeth, and he had considerable success with The Matchmaker, which most people know in its musical-comedy adaptation, Hello, Dolly!. Plus he penned the screenplay for one of Alfred Hitchcock’s best movies, Shadow of a Doubt.

Monday, February 8, 2021

Simply Sondheim: Breaking Through

|

| Emily Skinner and Solea Pfeiffer performing "Losing My Mind" and "Not a Day Goes By" in Simply Sondheim. |

Stephen Sondheim’s oeuvre has generated more musical revues than that of any other composer or lyricist in the history of the American theatre; I’ve seen at least eight of them. Simply Sondheim, which the Signature Theatre is streaming through the end of March, is the freshest, the most spirited and perhaps the best performed. Under the direction of Matthew Gardiner (who also choreographed), it’s presumably a necessarily pared-down version of a Signature production that Arlington, Virginia audiences saw in 2015, but it’s not on Zoom – it’s enacted on the Signature’s Manhattan stage, with musical director Jon Kalbfleisch conducting a small band behind a dozen singers. Its unadorned quality, in tandem with the presence of the camera, works to showcase the singers, not one of whom is less than admirable. Sondheim is famously demanding on vocalists, and a revue setting, where the numbers have been removed from their dramatic context, places an even tougher burden on them because of the complexity of the material and the intricacy of its link to its source. You don’t need to see South Pacific to understand the meaning of “This Nearly Was Mine”; it’s self-explanatory. But “Finishing the Hat” from Sunday in the Park with George or “The Worst Pies in London” from Sweeney Todd doesn’t stand alone, so anyone who performs it in an evening of Sondheim selections needs considerable acting skill to make sense of either of these songs for theatregoers. The knowledge of the legion of loyal Sondheim fans can only extend so far – and of course everyone in the audience isn’t likely to be an aficionado.

Wednesday, December 30, 2020

Facing History: The Human Countenance

“There are quantities of human beings, but there are even more faces, for each person has several.” – Rainer Maria Rilke

Everybody has one – or even several, according to the poet Rilke. But how often do we actually contemplate not only the handsomeness or beauty of a face, but just what having a face at all means in the first place, and how a face communicates something about us to others long before we even open our mouths? Naturally every culture has differing definitions for what makes an agreeable face stylistically, but all cultures can tell an angry face from a happy one, a serene and comfortable face from one that connotes rage or fear. A face is the most central equipment for expressing feelings and character we have access to, one usually accepted as a means of signifying intelligence and power as well as an unavoidable “window into the soul.”

In the marvelous book The Face: Our Human Story, primarily an art book from Thames and Hudson and the British Museum following a landmark exhibition of facial representations, Debra Mancoff shows us how the changing face of our face is actually also the human story writ large, not with words but with emotional expressions we all apply by using exactly the same identical ingredients: two eyes, a nose, two ears, a mouth, and the landscape in which they are all situated. As the book illustrates, with captivating illustrations and sculptures from every culture and through every historical epoch, our face is totally central to our cultural identity, which can vary drastically, but also simply to our shared human identity, which never does or can.

Monday, December 28, 2020

Sadness and Joy: A Christmas Carol

|

| Jefferson Mays in A Christmas Carol, available for streaming until January 3. (Photo: Chris Whitaker) |

There have been dozens and dozens of straight dramatizations of Charles Dickens’s 1843 tale “A Christmas Carol” – on stage, on film, on radio and television, even more if we include novelties like Mr. Magoo’s Christmas Carol (1962), The Muppet Christmas Carol (1992) and the 2017 parody A Christmas Carol Goes Wrong by the English company Mischief Theatre. Scrooged, the updated 1988 version, written by Mitch Glazer and Michael O’Donoghue and directed by Richard Donner, with Bill Murray as the avaricious president of a TV network, is a special case: an imaginative retelling of the story that captures its spirit with astonishing precision, just as Glazer’s contemporary take on Great Expectations did a decade later. It is, I think, sublime – and the best thing Murray has ever done.