|

| The False Mirror, by Rene Magritte, 1929. |

“Images, our great and primitive passion . . .” – Walter Benjamin, ca. 1930

Independent reviews of television, movies, books, music, theatre, dance, culture, and the arts.

|

| The False Mirror, by Rene Magritte, 1929. |

“Images, our great and primitive passion . . .” – Walter Benjamin, ca. 1930

|

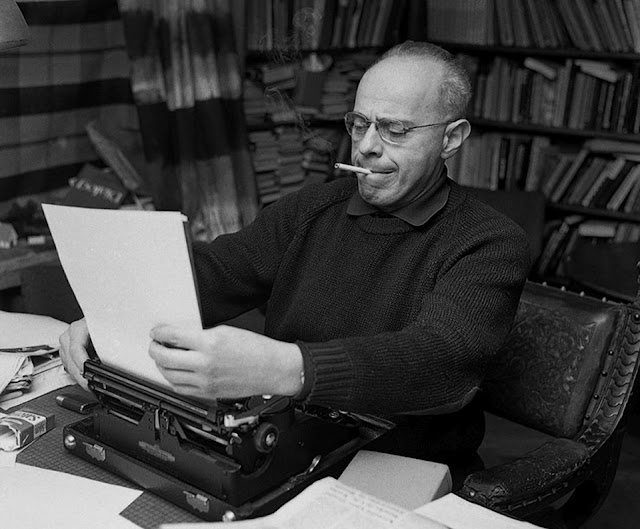

| Walter Benjamin at work in the National Library in Paris, 1937. (Photo: Gisèle Freund) |

“The dream has grown gray. The gray coating of dust on things is its best part. Dreams are now a shortcut to banality. Technology consigns the outer image of things to a long farewell, like banknotes that are bound to lose their value. It is then that the hand retrieves the outer cast in dreams and, even as they are slipping away, makes contact with familiar contours. . . . [W]hich side does an object turn toward dreams? What point is its most decrepit? It is the side worn through by habit and patched with cheap maxims. The side which things turn toward the dream is kitsch.” – Walter Benjamin, 1936Part One: Encountering the Aura

“By 'modernity,' I mean the ephemeral, the fugitive, the contingent, the half of art whose other half is the so-called eternal and the supposedly immutable . . . “ – Charles Baudelaire, poet of the inexpressible.It is very important, perhaps even crucial for some of us, that we come to have a full and clear grasp of what modernism actually was before even dreaming of approaching the thorny question of what so-called postmodernism might mean. Let’s not be too hasty here. Like most advanced forms of alternative thinking, at least on the surface, modernity emerged as a discussable notion during the mid-19th century in Europe, specifically France, which had already long established itself as a vanguard socially, politically and culturally, especially with the invention of the camera in about 1840. But also like most advanced ideas, the concept of the modern was imported by America and drastically enhanced before being blown up to global proportions.

In the context of art history, modernité, and the designation of modern art covering the early period from roughly 1860-1870, first entered the lexicon in the head, hands and pen of French poet Charles Baudelaire, whose 1864 essay entitled “The Painter of Modern Life” tossed his invented neologism like a conceptual hand grenade into the cultural marketplace. The radical symbolist poet, and possibly the first modern art critic, referred to “the fleeting, ephemeral experience of life in an urban metropolis and the responsibility which art has to capture and explore that experience.”

|

| left: Marina Tsvetaeva, 1925. (Photo: Roger Viollet); right: Nina Kossman (Photo: courtesy of American Pushkin Society) |

“A real translation is transparent; it does not cover the original, does not block its light, but allows the pure language, as though reinforced by its own medium, to shine upon the original all the more fully.” – Walter Benjamin, “The Task of the Translator,” 1921.

The Poets & Traitors Press series "seeks to showcase authors who travel between writing and translation" and "views translation as forming part of a continuum with the creative writer’s work". This imprint series began in 2013 and arose from the New York New School's translation workshop readings, which explored a shared format: featuring the original poems of translators of major poets alongside their translations of writers with whom they share a deep poetic resonance. Other Shepherds is the fifth book from Poets & Traitors, an independent press which continues to offer intriguingly hybrid books of poetry in conversation by a single author-translator.

|

| Harold Rosenberg: A Critic‘s Life by Debra Bricker Balken was published by University of Chicago Press in October. |

“At a certain moment the canvas began to appear to one American painter after another as an arena in which to act, rather than a space in which to reproduce or express an object. What was to go on the canvas was not a picture but an event.” – Harold Rosenberg

Oh, how I wish that this splendid new biography of one of my favourite art critics had been subtitled A Critical Life, if only to emphasize that he was both a critical thinker on the arts but also of critical importance to our shared contemporary culture in all its facets. It’s still splendid anyway, and I hope more people begin to appreciate how important he was to the modernist art discourse and also how prophetic he was in the formation of what people now ironically refer to as the postmodernist discourse. Hint: modernism has not gone away, nor has it been eclipsed. Rather, as Rosenberg’s superb prose indicated so clearly, its chief tenet, that of deconstructing the historical purpose and social meaning of art and embracing aesthetics only in the actual language that it uses to dismantle its own history, is merely in its late and mature phase. In other words, postmodernism, as Rosenberg surveyed it so vividly from his lofty perch as The New Yorker magazine’s art critic from 1967 until his passing, is simply finally doing what modernism was always designed to do: render utter subjectivity as the sole arbiter of any expressive visual language.

|

| Red Army II, 2022 digital print on metal, 48 x 48 inches. |

1. Singularity“Art ceases to be solely a form of self-expression alone in the electronic age. Indeed, it becomes a necessary kind of shared research and of internal probing.” – Marshall McLuhan, Through the Vanishing Point: Space in Poetry and Painting (1968).

The powerfully evocative and resonant works of Fatima Jamil are encountered by the entranced viewer as a truly nuanced hybrid of Eastern and Western traditions. In fact, it strikes me that they reveal a salient truth about the artistic urge to make images and our human appetite to absorb them into our nervous systems as a kind of remedy to the stresses of everyday living: the fact that there is no East or West in the immersive dimension of dreams. I instinctively refer to her otherworldly visions as icons, but not in the liturgical and canonical sense of that word, rather in the neutral sense of being iconic: a picture, image or other representation residing in analogy. She is also a visual storyteller par excellence.

|

| Andy Warhol and Brillo Boxes, the Stable Gallery, New York City, 1964. (Photo: Fred McDarrah) |

Richard Deming's new book Art of the Ordinary (Cornell University Press) explores a major revolution in the meaning of what art is and what it’s supposed to do. Its subtitle sums it up rather nicely: the everyday domain of art, film, philosophy and poetry. Cutting across literature, film, art, and philosophy, Art of the Ordinary is a trailblazing, cross-disciplinary engagement with the ordinary and the everyday. Because, writes Deming, the ordinary is always at hand, it is, in fact, too familiar for us to perceive it and become fully aware of it. The ordinary, he argues, is what most needs to be discovered and yet can never be approached, since to do so is to immediately change it.

“Images, our great and primitive passion . . . ” – Walter Benjamin, ca. 1930

“Politics is the art of the possible, the attainable – the art of the next best thing.” – Otto Von Bismarck

“Politics is the entertainment branch of industry.” – Frank ZappaThroughout the crucible of recorded history, politics has always undergone a dramatic shift in form, focus and intent with each new technological development. But today, its very core definition has practically altered beyond recognition since the advent of the digital domain we currently inhabit. Towards the end of the 20th century, a century of the most drastically amplified creative inventiveness and the most viscerally enhanced horrors, approximately around 1998, in fact, we entered a realm almost as theatrically shape-shifted as the transition from the medieval period to the so-called Renaissance. Technics, the skillful utility of tools, has always been the hallmark for every decisive change in our concept of reality as sentient beings. Now, however, reality has blurred irrevocably.

|

| Stanisław Lem, Kraków, 1971. (Photo: Jakub Grelowsk) |

As for me, I am busy pointing my telescope through the bloody mist at a mirage of the nineteenth century, which I am trying to reproduce based on the characteristics that it will manifest in a future state of the world, liberated from magic. Of course, I first have to build myself this telescope. — Walter Benjamin, letter to Werner Kraft, October 1935.

As for Lem, from about 1956, when many of his most visionary stories and novels began to flow freely from his pen, although not always yet translated from his native Polish tongue into our anxious English, up to 2006, when he shuffled off his mortal coil, he navigated a truly vertiginous course through multiple literary genres at a prodigious rate. The least accurate way to describe him is the one he is best known for, being a science fiction author, while the most accurate characterization, for me at any rate, is as a purveyor of unclassifiable speculative fiction. The only author whom he really can be compared with is Aldous Huxley, creator of the harrowing dystopian opus Brave New World in 1931. Thirty years after Huxley, with the release of the brilliant work for which Lem is best known, Solaris, I believe he entered that pantheon of great forecasters and futurologists who warned us where we were all going by pointing out, poetic telescope in hand, that we were already there.

|

| Marsupial, 2013, by Mowry Baden. (Steel aluminum fabric rubber. Image: VAG) |

|

| Cheap Sleeps Columbine,1994. (Mattress boxspring, pillow fabric, wood, mirror. Image: VAG) |

|

| Tachyardia, 2016. (Rubber and steel. Image: VAG) |

– Donald Brackett is a Vancouver-based popular culture journalist and curator who writes about music, art and films.He is the author of the book Back to Black: Amy Winehouse’s Only Masterpiece (Backbeat Books, 2016). In addition to numerous essays, articles and radio broadcasts, he is also the author of two books on creative collaboration in pop music: Fleetwood Mac: 40 Years of Creative Chaos, 2007, and Dark Mirror: The Pathology of the Singer-Songwriter, 2008, and is a frequent curator of film programs for Pacific Cinematheque. His latest book is Long Slow Train: The Soul Music of Sharon Jones and The Dap-Kings, published in November 2018. His new book, Tumult! The Incredible Life and Music of Tina Turner, is forthcoming from Backbeat Books in 2020.

– Donald Brackett is a Vancouver-based popular culture journalist and curator who writes about music, art and films.He is the author of the book Back to Black: Amy Winehouse’s Only Masterpiece (Backbeat Books, 2016). In addition to numerous essays, articles and radio broadcasts, he is also the author of two books on creative collaboration in pop music: Fleetwood Mac: 40 Years of Creative Chaos, 2007, and Dark Mirror: The Pathology of the Singer-Songwriter, 2008, and is a frequent curator of film programs for Pacific Cinematheque. His latest book is Long Slow Train: The Soul Music of Sharon Jones and The Dap-Kings, published in November 2018. His new book, Tumult! The Incredible Life and Music of Tina Turner, is forthcoming from Backbeat Books in 2020.

|

| I Don’t Know Anything / I Know Nothing by Marija Jaukovic (2015, oil on panel 4 x4 ft.) |

|

| Contre-Jour (Backlight) 2009/Festival of Gijon, 2010. |

“Images, our great and primitive passion . . .” – Walter Benjamin, ca. 1935.

“Your camera is the best critic there is. Critics never see as much as the camera does. The camera is more perceptive than the human eye.” – Douglas Sirk, 1955.

|

| Between Dreaming and Living #8, by Vikky Alexander. (Image: VAG) |

|

| When the Real Day Breaks, by Dénesh Ghyczy, 2018, 130 x 170 cm. |

“The painter should paint not only what he has in front of him, but also what he sees inside himself. If he sees nothing within, then he should stop painting what is in front of him.”

– Caspar David Friedrich

|

Trying So Hard by Bianca Biji,. (2015, 31 x

44 cm.)

|

"The minute atom has as many degrees of latitude and longitude as the mighty Jupiter."Two forms of human communication immediately come to mind when viewing the incisive and dramatic abstract paintings of the Belgian artist Bianca Biji: sign language and calligraphy. In their deft command of a strong but silent gestural language that is both classically modernist and cheekily postmodern at the same time, her paintings summon what Harold Rosenberg in the late '40s and '50s called “action painting.” But they breathe new life into the visceral theatricality of her legitimate precursors, Kline, Tobey and Miró, by injecting fresh fuel to the ongoing fire – especially the sublimely smoldering embers of Franz Kline. It is not at all a negative thing to say that her work engages in a striking visual conversation with Kline in the best possible way: as optical poems.

– James Lendall Basford

“Images, our great and primitive passion . . .”Some artists loom so large on our cultural landscape that their shadow covers everyone who comes after them, and indeed, some heavyweights even obscure the very aesthetic horizon that they themselves helped to construct. The artists of the 20th century who can be said to be so influential and impactful, so important to the vernacular we use to even discuss art now, that their presence made possible the clearings in which whole clusters of others congregate stylistically can almost be counted on the fingers of one hand. Naturally enough, which fingers depends on which hand, but after much consideration it seems plausible that a scant few were so gargantuan in their production of new visual values that one can literally trace the branches of the artistic family trees they planted.

“The dream has grown gray. The gray coating of dust on things is its best part. Dreams are now a shortcut to banality. Technology consigns the outer image of things to a long farewell, like banknotes that are bound to lose their value. It is then that the hand retrieves the outer cast in dreams and, even as they are slipping away, makes contact with familiar contours. Which side does an object turn toward dreams? What point is its most decrepit? It is the side worn through by habit and patched with cheap maxims. The side which things turn toward the dream is kitsch.”

– Dream Kitsch, Walter Benjamin ca. 1930.

|

| Chuck Samuels: Becoming Photography (Kerber Verlag, 2021). |

“From the idea that the self is not given to us, I think there is only one practical consequence: we have to create ourselves as a work of art.” – Michel Foucault

Much of what we now define as the poetics of images, the aesthetics of the camera, and the politics of photography comes to us from the thoughtful pens of cultural theorists such as the German critic Walter Benjamin, the French philosopher Roland Barthes, the American polemicist Susan Sontag, and the British art historian John Berger. Their speculations on what makes photography not only an art form but a special and privileged form of modernist consciousness have paved the way for a deep appreciation of both the magic potential and the seductive powers of technological reproduction. Our ways of seeing and thinking about seeing have often been guided by their ruminations on what happens when we photograph something or someone, and their penetrating analysis of the photographic arts has inspired and influenced generations of image-makers.

|

| No 2. (2020), acrylic, Plexiglas, goldleaf on aluminum, 8 x 8 inches (Odon Wagner Gallery). |

“If we keep our eyes open in a totally dark place, a certain sense of privation is experienced. The organ is abandoned to itself, it retires into itself. That stimulating and grateful contact is wanting by means of which it is connected with the external world.” – Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Theory of Colours (1810).

Some viewers and readers may recall earlier bodies of work by Michael Burges executed in reverse painting on glass, a resistant surface which allowed us to look through to get at, and an intriguing strategy devised to liberate the artist from the acres of textile and canvas customarily used by painters throughout art history, those who formally celebrated its absorbent and tactile qualities. With these new works, this painter continues to explore reverse glass painting mounted on aluminum, an equally resistant and reflective surface capable of carrying the subtle language of his images of time-soaked light as a most effective medium. Our eyes themselves are now the delicate textiles which absorb their fleeting messages, if we allow their mesmerizing gaze back at us.