Independent reviews of television, movies, books, music, theatre, dance, culture, and the arts.

Sunday, June 22, 2025

Berlin Alexanderplatz: Döblin Meets Fassbinder Meets Lewis

“It’s only because of their stupidity that they are able to be so sure of themselves.”

--Franz Kafka (to Max Brod)

Not so long ago I was discussing the compelling and distressing works of four Japanese novelists in terms of a special category I rashly called the scariest narratives ever written. And while it’s true that Kenzaburo Oe, Osamu Dazai, Kobo Abe and Yukio Mishima are right up there in terms of writing seemingly elegant and restrained tales while secretly scraping off the thin psychological veneer of civilization to reveal the throbbing savagery beneath, now I might have to retract my assessment in light of recent re-readings of two novelists who are even more pertinent and sadly applicable to these harrowing times we’re all trying to live through. They were written historically close to each other, one by a German author, Alfred Döblin in 1929, when his country was witnessing the demise of the wistful Weimar Republic and the rise of National Socialism, while the other was an American novelist in 1935, Sinclair Lewis, who was witnessing a threat to his own country’s democratic principles under the paranoid banner of white nationalism.

Saturday, March 8, 2025

Primal Screen Therapy: The Optical Unconscious Writ Large

“The screen is a magic medium. It has such power that it can retain interest as it conveys emotions and moods that no other art form can ever hope to tackle."

--Stanley Kubrick

--Federico Fellini

Culture critic Walter Benjamin once remarked that the invention of the camera introduced us to unconscious optics, just as Freud’s invention of psychoanalysis did for unconscious impulses, and he knew whereof he spoke. That insight reveals the same prescience that Freud’s chief acolyte and primary competitor Carl Jung also sensed, in a somewhat more refined and spiritual manner: that cinema is the artful language of dreams we speak while we’re still awake. Two insightful books, American Avant-Garde Cinema’s Philosophy of the In-Between by Rebecca Sheehan and Screening Fears: On Protective Media by Francesco Casetti, share an equally insightful exploration of the archetypal and collective mythologies that define classic cinema regardless of its genre. Looking at films through a psychological lens provides us with a valuable map and a discursive language which we can use to orient ourselves within the imaginal landscape of the motion picture art form. These two books, with a kind of cogent synchronicity, also definitely offer a deep dive into cinema as the quintessential art form of the 20th century. They deftly penetrate our shared psychic myths as revealed through the language of films and thus help us to more deeply understand our own hopes and fears while doing so, and as such they supply a kind of primal screen therapy which assists the audience in conversing with our own optical unconscious.

Friday, April 12, 2024

Cry Me a River: The Sweet Sorrow of Film Noir

“Life is a tragedy when seen in a close-up, but a comedy when seen in the long shot.” – Charlie Chaplin

Melodrama: the essential link between classical tragedy and ‘dark film’. “Suffering, with style” is the succinct and totally apt way that Turner Classic Movies curator Eddie Muller characterizes this unique mode of film noir storytelling: “The men and women of this sinister cinematic world are driven by greed, lust, jealousy and revenge, which leads inexorably to existential torment, soul crushing despair and a few last gasping breaths in a rain soaked gutter. But damned if these lost souls don’t look sensational riding the Hades Express. If you’re going straight to hell, you might as well travel with some style to burn.”

From the moment the term film noir or dark film was first employed by advanced French critics in the post-World War Two global culture, there was also an instant debate about what it encapsulated so vividly. Muller, who is also an author of crime fiction himself, further defines the concept as being about a protagonist who, driven to act out of some desperate desire, does something that he or she knows to be wrong, even understanding what dire consequences will follow. Karma always looms large in noir.

Thursday, October 26, 2023

In the Labyrinth: Picasso’s Graphic Work

|

| Lucien Clergue, Portrait (1956). |

“Mystery is the essential ingredient of every work of art.” – Luis Buñuel

Who and what do we see when we study the splendid photographic portrait of Pablo Ruiz Picasso captured by the esteemed Lucien Clergue in1956, when the Spanish artist was at the height of his powers? Having been adopted as a global cultural citizen beyond all mere geographical borders, the words who and what are both applicable in his unique case, as someone who was as vital and revolutionary in painting as his countryman Cervantes was in literature three hundred years earlier. So when Clergue memorialized that dramatic face, some four decades after the artist first reinvented the history of art at the turn of the last century, recasting it in his own image by collaborating with Georges Braque in the revelation of Cubism, and with roughly another two tumultuous decades still remaining in his titanic aesthetic mission, what sort of portrait telegram did the photographer manage to send us all in the future, and yet further into the future of the future? His portrait seems to whisper: behold, a living archetype.

Picasso’s elusive and mercurial character, a persona he appeared to perform as if he lived on a stage, still has the capacity to allure and amaze us. With good reason, and these powerful works on paper assembled here are an accurate indication of exactly why. He was a towering figure who looms large in both the art world and the world of popular culture, a gargantuan artist beyond most limits and even any definitions. Gazing at the overwhelming confidence in the awesome face of the man behind these prints, I am often reminded of the words of a favourite Brazilian author, Clarice Lispector: “He had the elongated skull of a born rebel.” I do hope so, Clarice, but all the landforms of his skull grew inward, like stalagmites, rather than upward and out. His Guernica painting from 1937 was one such interior landform, but then, so are his many masterful prints: each one is a mountain peak in reverse on paper, a spritely graphic Everest.

Tuesday, May 9, 2023

Reveries Unlimited: The Razor’s Edge Stories of Karl Jirgens

|

| Porcupine’s Quill Press, 2022. |

"There is something missing . . . if I knew what it is then it wouldn't be so missing . . . " – Hans in The Recognitions by William Gaddis (1955).

No, Reveries Unlimited is not the corporate name of a company specializing in providing services related to waking dreams, dreams we have with our eyes wide open while engaging in psychological wanderings. I’ve coined this hopefully supple phrase to encapsulate the kind of author who prompts, encourages, inspires and otherwise seduces us into sharing his or her narrative roamings through a past, present and future which collide, intersecting gently in a series of gently linked stories. Such is the service provided by Karl Jirgens in the recent collection called The Razor’s Edge, from Porcupine’s Quill Press, which subtly touches upon Maugham’s classic tale of a search for the meaning of life, in which we often feel as if we were walking on that precarious edge, posed between transcendence and a fall into oblivion.

Thursday, April 20, 2023

Double Vision: Beyond Binary Art History

|

| Princeton University Press (2022); Princeton University Press (2022) |

“We have arrived at an era of humans and their doubles. We no longer need mirrors in order to talk to ourselves.” –Jean-Luc Godard, 1965.

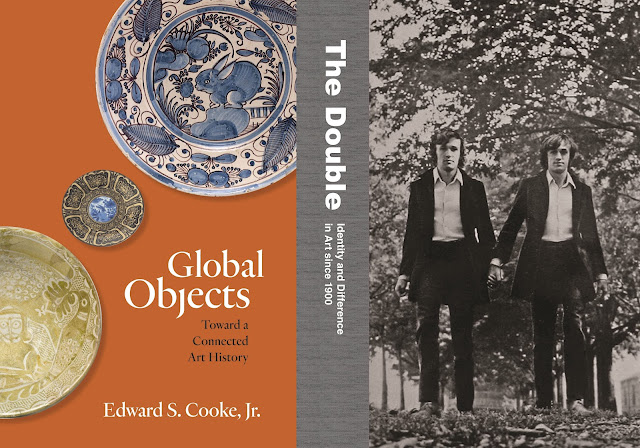

Polarity, duality, dichotomy, opposition, contradiction, mutuality: these art books run the gamut of this spectrum.

As almost always in my case, synchronicity appeared to be at play (in its usual subterranean manner) with the arrival of two remarkably insightful books that explore our binary condition and what lies beyond it, each in its own distinctive way, but both in shared terms of expanding our appreciation for art and cultural artifacts which transcend outmoded definitions of traditional media disciplines and aesthetic values. Global Objects: Towards a Connected Art History, by Edward Cooke, and The Double: Identity and Difference in Art Since 1900, by Peter Meyer, are excellent in-depth explorations of how contemporary art provides a mirror of reality, even when that mirror is clouded by myth or fixation. Both are released by Princeton University Press and both approach the polarities of art versus craft and the dichotomies of singular self, with a deft command of their subject matter and theme.

Sunday, March 26, 2023

Haptic Happiness: Analog as Allegory

“Ever since Adam, who has really gotten the meaning of this great allegory—the world?”– Herman Melville, 1851

“Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.”– Arthur C. Clarke, 1968

In “The Machine Stops,” a short story written by E.M. Forster in 1909, the famed novelist surprised the many lovers of his compelling but still conventional fiction, highly regarded tomes such as A Room With a View, A Passage to India, Maurice, and Howards End, by taking a radical detour into the kind of speculative fiction most often associated with science and its limits. He went on a similar jaunt in 1914 with his collection of stories called The Eternal Moment, which explored parallel science fiction themes and supernatural speculations. Throughout his lengthy writing career, during which he lived long enough to witness humans landing on the moon, he frequently alternated between entertaining social observation writing and the vividly imaginative ideas he explored in his wildly cerebral Celestial Omnibus. In fact, “The Machine Stops” was so utterly astonishing largely due to its surmise, nearly a century before the internet even existed as a concept, that we might eventually occupy, via technics (the original and official word for technology), a world where we are interconnected through a threshold-breaking mechanical means which starts out as a benevolent helper but invariably ends up virtually colonizing our very definition of reality.

Wednesday, November 30, 2022

Long Distance Operator: The Visionary Writing of Stanislaw Lem

|

| Stanisław Lem, Kraków, 1971. (Photo: Jakub Grelowsk) |

As for me, I am busy pointing my telescope through the bloody mist at a mirage of the nineteenth century, which I am trying to reproduce based on the characteristics that it will manifest in a future state of the world, liberated from magic. Of course, I first have to build myself this telescope. — Walter Benjamin, letter to Werner Kraft, October 1935.

As for Lem, from about 1956, when many of his most visionary stories and novels began to flow freely from his pen, although not always yet translated from his native Polish tongue into our anxious English, up to 2006, when he shuffled off his mortal coil, he navigated a truly vertiginous course through multiple literary genres at a prodigious rate. The least accurate way to describe him is the one he is best known for, being a science fiction author, while the most accurate characterization, for me at any rate, is as a purveyor of unclassifiable speculative fiction. The only author whom he really can be compared with is Aldous Huxley, creator of the harrowing dystopian opus Brave New World in 1931. Thirty years after Huxley, with the release of the brilliant work for which Lem is best known, Solaris, I believe he entered that pantheon of great forecasters and futurologists who warned us where we were all going by pointing out, poetic telescope in hand, that we were already there.

Wednesday, July 20, 2022

The Anxious Object: The Sublime Void and Art in the Age of Anxiety

|

| The Sublime Void (Ludion Press, Antwerp / DAP, 1993); Art in the Age of Anxiety (MIT Press/Morel Books, 2021) |

“Perhaps it was always like this. Perhaps there was always a vast alien expanse between an epoch and the great art which it produced. What distinguishes works of art from all other objects is the fact that they are, as it were, things of the future, things whose time has not yet come.” – Rainer Maria Rilke.

“Art in the age of anxiety explores the ways in which everyday devices, technologies and networks have altered our collective consciousness. We are all living in an age where anxiety has become a part of our daily life.” – Omar Kholeif, curator.

When my wife Dr. Mimi first gave me these two books as a birthday gift, it was not immediately apparent how intimately connected, as if by some subterranean river of meaning, both of them were to me in the present, nor how substantially that meaning would expand exponentially over time to encompass almost every aspect of what tenuously living in both the 20th and 21st centuries actually might signify. That gift might just be the unexpected case where profundity drops down on us, apparently carried on winds that at first are not quite even discernible by us, until later on, one day, it comes crashing through the roof of our skulls and rearranges the furniture in our minds.

Thursday, May 26, 2022

Otherworldly: The Haunting Icons of Fatima Jamil

|

| Red Army II, 2022 digital print on metal, 48 x 48 inches. |

1. Singularity“Art ceases to be solely a form of self-expression alone in the electronic age. Indeed, it becomes a necessary kind of shared research and of internal probing.” – Marshall McLuhan, Through the Vanishing Point: Space in Poetry and Painting (1968).

The powerfully evocative and resonant works of Fatima Jamil are encountered by the entranced viewer as a truly nuanced hybrid of Eastern and Western traditions. In fact, it strikes me that they reveal a salient truth about the artistic urge to make images and our human appetite to absorb them into our nervous systems as a kind of remedy to the stresses of everyday living: the fact that there is no East or West in the immersive dimension of dreams. I instinctively refer to her otherworldly visions as icons, but not in the liturgical and canonical sense of that word, rather in the neutral sense of being iconic: a picture, image or other representation residing in analogy. She is also a visual storyteller par excellence.

Thursday, March 24, 2022

Post-What: Just What Was Modernism, Anyway?

“By 'modernity,' I mean the ephemeral, the fugitive, the contingent, the half of art whose other half is the so-called eternal and the supposedly immutable . . . “ – Charles Baudelaire, poet of the inexpressible.It is very important, perhaps even crucial for some of us, that we come to have a full and clear grasp of what modernism actually was before even dreaming of approaching the thorny question of what so-called postmodernism might mean. Let’s not be too hasty here. Like most advanced forms of alternative thinking, at least on the surface, modernity emerged as a discussable notion during the mid-19th century in Europe, specifically France, which had already long established itself as a vanguard socially, politically and culturally, especially with the invention of the camera in about 1840. But also like most advanced ideas, the concept of the modern was imported by America and drastically enhanced before being blown up to global proportions.

In the context of art history, modernité, and the designation of modern art covering the early period from roughly 1860-1870, first entered the lexicon in the head, hands and pen of French poet Charles Baudelaire, whose 1864 essay entitled “The Painter of Modern Life” tossed his invented neologism like a conceptual hand grenade into the cultural marketplace. The radical symbolist poet, and possibly the first modern art critic, referred to “the fleeting, ephemeral experience of life in an urban metropolis and the responsibility which art has to capture and explore that experience.”

Wednesday, December 29, 2021

The Bearable Darkness of Being: Teju Cole’s Words and Images

| |

|

“Objects have the longest memories of all. Beneath their stillness, they are alive with all the terrors they have ever witnessed.” – Teju Cole, New York Times, 2014

I – Setting the Stage

Teju Cole’s riveting new book of inspiring essays, Black Paper, published by the University of Chicago Press, is the latest gift from his fruitful and ever-accelerating career as one of our premiere culture critics. For several years he was the photography critic for The New York Times Sunday Magazine, a prestige posting from which he surveyed our world with sheer poetic clarity. Like many other people, one of the great joys in my life has been allotting a certain amount of time, variable depending on mood, to settling in for the duration needed to read the Sunday edition. Literally doing nothing for long enough to actually simply live, without any purpose at all other than traveling through the words and images elegantly and eloquently being presented in the frequently obscenely fat and multi-sectioned contents of the newspaper of record. Just lugging it home is enough to make me feel like I’ve won a survival contest whose reward is the pleasure of idleness for about two hours. The official word for this practice is, of course, reverie.

And each of us fortunate to be able to indulge in such relatively harmless pleasures has a certain strategic approach to reading it: how to begin, where to start, in what order, which section of which department, and so on. In my case, the first thing I separate out from the obese pile of newsprint (still such an analog joy in today’s gruesomely online digital world: news that actually comes off on your fingertips in vast dark smears) is the Sunday Magazine. There again, an opulent abundance awaits the reader, whether it be fashion, food or furniture. For me, it’s a seemingly humble little column in the up front section called “On Photography,” written by the breathtakingly gifted image maker and thinker Teju Cole. In my opinion, he is a national treasure. Unless you knew it was there, his regular column, which used the same name as a famous 1977 book of essays on photography by the great Susan Sontag, might be easy to glide right past in your search for end-of-week distraction. Once discovered, however, it was a must-see/read destination. It’s deceptively discreet presentation, generally a single quotidian image accompanied by about a page and a half of simmering type, also practiced a similar craft espoused by Sontag, that of ekphrasis, the poetic expression of emotive texts in direct personal response to works of visual art, in this case photographs.

His quietly poetic style was absolutely perfectly manifested to arrest the reader/viewer for far longer than you may have thought possible at first. The quote used above, for instance, has stayed with me on my writing desk for seven years and confronts me daily with an awareness that is nearly confounding in its emotive depths. The only other writers capable of achieving that kind of utter resistance to absorption are perhaps different in each of our lives, W.G Sebold and David Foster Wallace in mine, for instance, but the skilled surfing of the meanings hiding inside things is a shared ability you have to have been born with. Cole is so accomplished in both his chosen arts, images and words, that he’s overwhelming in a kind of shy and almost retiring, reticent way (he is what my late father used to call ‘scary brilliant’) and also so seductive that once you know he was there, embedded amongst the early ads in the magazine like a simmering bomb of beauty, you started to explore his other means of expression and find to your astonishment that he has also exhibited his own photographs with drastic success and written reflections on being absolutely alive in repeated forays into published essays that have created a formidable edifice.

Scary brilliant, and it is rare for a practitioner of an art such as fabricating the frozen music of images to also be so singularly adept at being a culture critic who can so fluidly explore the beauties or terrors of his peer photographers that one feels invited into a secret cult of sorts: the place where the rituals of aesthetic aura are being celebrated in ways that also bring us perilously close to actually understanding the meaning of such terms as affect, the power of emotional impact in action, and agency, the power of taking action in the world based on privately cultivated propulsion. Alas, Cole was the photography critic for The New York Times Magazine only from 2015 to 2019, and I’ve missed him every Sunday since. But he’s also, fortunately for me and his other followers, been very busy elsewhere, and now has the extra time away from a weekly column to exhibit his own work as well as dive deeper into our visual culture as an astute assessor of our precarious life in the 21st century.

In a review in Feature Shoot Magazine of a Cole solo exhibit, the critic Miss Rosen observed with an acute eye and mind just what makes him so special for so many of us:

The relationship between image and text is one of the most challenging pairings to exist. They demand complete attention and so one must choose: to look or to read—and in what order? Perhaps it seems deceptively simple: one simply does as they are inclined. Yet regardless of preference, they inform each other, infinitely. When we read, we see the picture in our mind. When we look, we write the words ourselves. Now we are asked to forgo our imagination and focus on the given context. Yet few can bridge the gap that exists between the linguistic and visual realms, the distinctive forms of intelligence that operate independently and interdependently at the same time. Most often, we simply opt out somewhere along the line, wanting to return to the freedom to imagine for ourselves rather than listen to what we are told. Writer Teju Cole understands this well. As photography critic for The New York Times Magazine, Cole mastered the painting of pictures with words that illuminate and elucidate in equal part, so that his words both add and peel back layers from that which appears before our eyes.

In his first solo show in 2017, Blind Spot and Black Paper, at Steven Kasher Gallery, New York, the writer brought us along for a journey around the world, looking at life not only through his eyes but experiencing it through his prose. The exhibition, which accompanied the publication of his fourth book, featured a selection of 30 color photographs accompanied by a single paragraph. Each piece of text is a beautifully encapsulated prose poem that draws us into uncharted depths, giving voice to the image that quietly beckons us with its simple, subtle lyricism of color, shape, and form.

And that insight of his into the stillness of objects and their memory that so impacted me, with places actually being just bigger objects, is richly evident in many of his ekphrastic experiments, as demonstrated so well when we travel through some of his powerful images and evocative words.

|

| Brienzerzee, from Fernweh (2014, Stephen Kasher Gallery, NY) |

I opened my eyes. What lay before me looked like the sound of the alphorn at the beginning of the final movement of Brahms’s First Symphony. This was the sound, this was the sound I saw.

|

| Zurich, from Fernweh, (2014, Stephen Kasher Gallery, NY) |

Stillness. In the interior, she reads with lowered eyes, unaware of what comes next. A presence made of absence.

|

| Zurich, from Fernweh (2015, Stephen Kasher Gallery, NY). |

I sat there for hours and watched the sun slip across the landscape. Anything can happen. The point is to shatter serenity; the absurdity of contrast between before and after is the very point

|

| Zurich, from Fernweh (2014, Stephen Kasher Gallery, NY). |

You take around 7500 steps each day. If you live to eighty, that comes to 200 million steps over the course of your life, a hundred thousand miles. You don’t consider yourself a great walker, but you will have circumnavigated the globe on foot four times over.

II – Staging the Play

Teju Cole is as versatile as he is prolific. A novelist, photographer, critic, curator and the author of seven tantalizing books, among them Open City, Blind Spot, Golden Apple of the Sun, Fernweh, and his latest one, Black Paper, he was a 2018 Guggenheim Fellow, and is currently the Gore Vidal Professor of the Practice of Creative Writing at Harvard. Based on even that snapshot of his résumé, and my reading of his ruminations over the course of many rewarding years, one thing I know for certain is that it is virtually impossible for Professor Cole to teach any other living human being how to write the way he does. His style is so graceful, elliptical, digressive, entertaining and educational, even or especially for the average lay reader, that I’m pretty sure all his lucky students can really do is keep their mouths shut and hope to somehow soak up some of his splendour, perhaps by osmosis. And Black Paper feels like a little way station in a snowy niche on the way to the top of a mountain range where spookily gifted writers such as Walter Benjamin or Harold Rosenberg go on vacation. It is also almost a work of theatre, not because it is in any way theatrical, but rather because the scope of its sweep, into and out of a vertiginous array of subjects and themes, has an epic-tragedy kind of vibe about it.

Characterizing him as “a kind of realm” in The New York Review of Books, Norman Rush summed up Cole’s mission quite nicely: “Teju Cole is an emissary for our best selves. He is sampling himself for our benefit, hoping for enlightenment and seeking to provide pleasure to us through art.” The key notion here is that of sampling, usually a musical term for collaging different fragments of different musical sources into a unified score, frequently one with a hip-hop flavour. That active aspect of mixing, matching and merging is precisely what Cole does in most of his works, whether on images or on social and cultural issues, and especially as conducted in Black Paper, perhaps the most far-ranging, diverse and multi-faceted sampling of his acutely aware experiences of our postmodern world yet.

His bicultural origins – he was born in America in 1975, raised in Nigeria until he was 17 and brought back to America with his family to study art and then medicine, before returning abroad to study African art history and Northern Renaissance art at Columbia U. in New York, serving as writer-in-residence at Bard College and writing a flurry of novels – have all accumulated the perfect amount of intellectual gravitas and cosmopolitan charm to gracefully, i.e., effortlessly, startle us with a truly polyglot stew of knowledge. He stirs this dreamy stew ideally in Black Paper, where he declares, “Darkness is not empty.” as he proceeds to navigate his way through a variety of meditations on what it means to maintain our humanity in a time of darkness. One solution, he has suggested here, is to be intensely attentive to our experience, so much so that it’s not so much about seeing what’s going on, to take it all in, but also to consider what it is we’re not seeing and what is not happening, but which should be.

The essays in this new collection, ranging across five separate parts, commencing with a masterful consideration about what makes the Italian painter Caravaggio so important, through territories he calls “Elegies” (containing great insights into the image historian John Berger and cultural historian Edward Said), “Shadows” (containing clear glimpses into the work of artists Kerry James Marshall and Lorna Simpson), “Coming to Our Senses” (with skillfully clarifying approaches to ethics) “In a Dark Time” (with touching portraits of refusal, resistance, and cooperative living) and “Epilogue: Black Paper” (a stirring counterpoint to Caravaggio which abstractly explores the links between literature and activism while still remaining a deeply humanist document). Along the way, he also manages to make manifest the power of the colour black in the visual arts and the role of the shadow in photography. The last section also contains one of the most heart-wrenchingly simple observations about our shared harrowing time that I’ve read in ages: “An incalculable number of people cried themselves to sleep in those days.”

What’s a premiere photography critic doing writing about the painting of Caravaggio, you might well ask? Well, first of all, Cole is so eloquent that he could write about the history sheep farm fences and make it transformative and compelling, and after all, the subtitle of his new book is Writing in a Dark Time, which brings us to Caravaggio in the most logical of ways. Caravaggio, apart from leading a tragic life, dying young, influencing every painter after him, and in the cauldron of his own feverish brain practically inventing the Baroque style in art, was utterly immersive in a manner consistent with our present era. He was also among the first exponents of complete subjectivity in art, one of the hallmarks of our own age, and he skillfully indulged his own private obsessions practically to the exclusion of all else. Most importantly, perhaps, Caravaggio was photography. For the roughly 250 years from Caravaggio to the French invention of the camera in about 1840, his representational style was the main means of producing mimetic memorials to actuality.

Cole, an accomplished novelist as well as essayist, not only knows this but also acts upon it, by bookending his approach to Caravaggio with his appreciation of a contemporary such as Lorna Simpson, an American conceptual photographer and multimedia artist whose radical works on paper extended the exploration of representation, identity and history. In some strange ways, apart from the shift from painting to photography, she is examining the edges of perception in precisely the same way that Caravaggio did. Cole also reminds us of what the novelist Mary Gaitskill stressed so well: “Fiction is to literal representation what painting is to photography: it’s just not claiming to be ‘real’ in the same way at all.” And it is precisely because Cole himself blurs the arbitrary lines between fiction, essay, poem, elegy, document, social activist, artist and critic that he is able to stride so confidently across the landscape of subjects and themes in this new book. He thus approaches the drastically fractured moment in history we currently occupy via a stunning constellation strategy: discussing the confrontation with the parallel arcs of unsettling art in unsettling times from every possible angle.

Unsettling, yes. Here is why we need to nourish ourselves on Cole’s proteins, whose own images are strong but whose words are even stronger, once again reflecting on the traveling vitamin called Caravaggio:

Porto Ercole was the final unanticipated stop. He’s buried somewhere there. But his real body can be said to be elsewhere: the body, that is, of his painterly achievement. He was a murderer, a slaveholder, a terror and a pest. But I don’t go to Caravaggio to be reminded of how good people are, and certainly not because of how good he was. To the contrary: I seek him out for a certain kind of otherwise unbearable knowledge. Here was an artist who depicted fruit in its ripeness and at the moment it has begun to rot, an artist who painted flesh at its most delicately seductive and its most grievously injured. I don’t have to know him to know that I need to know what he knows, the knowledge that hums, centuries later, on the surface of his paintings, knowledge of all the pain. Loneliness, beauty, fear and awful vulnerability our bodies have in common.

|

| Caravaggio, Flagellation of Christ (1607, Naples). |

See what I mean? Our own weird time often seems as dark of Caravaggio’s time was, which is why he still matters, since he seems to know us almost more than we know ourselves, and even at least as much as a contemporary artist such Kerry James Marshall does. They are both, as Cole so deftly demonstrates, about repentance, atonement, reconciliation and redemption. Caravaggio knew he needed to repent, in fact he was repenting almost every twenty minutes, and he especially repented in each painting, while Marshall masterfully reminds us, especially white culture, that it is high time for the rest of us to repent as well. In a hundred years, if there were to still exist an archive of memory such as the famed Encyclopedia Britannica, and that’s a big if, one can easily imagine a single entry capable of adequately covering and capturing the strange years between 2020 and 2022. And that entry would have been written by Teju Cole in Black Paper: Writing in a Dark Time:

Many fell ill, illnesses that showed on the face and illnesses that didn’t. We knew and we didn’t know. Poverty began to burrow into those lives. Shame made a home in some people, some went hungry, hunger hollowed them out. The stock market was up, but many pockets were empty.

– Donald Brackett is a Vancouver-based popular culture journalist and curator who writes about music, art and films. He has been the Executive Director of both the Professional Art Dealers Association of Canada and The Ontario Association of Art Galleries. He is the author of the recent book Back to Black: Amy Winehouse’s Only Masterpiece (Backbeat Books, 2016). In addition to numerous essays, articles and radio broadcasts, he is also the author of two books on creative collaboration in pop music: Fleetwood Mac: 40 Years of Creative Chaos, 2007, and Dark Mirror: The Pathology of the Singer-Songwriter, 2008, as well as the biographies Long Slow Train: The Soul Music of Sharon Jones and The Dap-Kings, 2018, and Tumult!: The Incredible Life and Music of Tina Turner, 2020. His latest work in progress is a new book on the life and art of the enigmatic Yoko Ono, due out in early 2022.

Friday, December 10, 2021

Critique of a Critic’s Critic: Harold Rosenberg Looms Large

|

| Harold Rosenberg: A Critic‘s Life by Debra Bricker Balken was published by University of Chicago Press in October. |

“At a certain moment the canvas began to appear to one American painter after another as an arena in which to act, rather than a space in which to reproduce or express an object. What was to go on the canvas was not a picture but an event.” – Harold Rosenberg

Oh, how I wish that this splendid new biography of one of my favourite art critics had been subtitled A Critical Life, if only to emphasize that he was both a critical thinker on the arts but also of critical importance to our shared contemporary culture in all its facets. It’s still splendid anyway, and I hope more people begin to appreciate how important he was to the modernist art discourse and also how prophetic he was in the formation of what people now ironically refer to as the postmodernist discourse. Hint: modernism has not gone away, nor has it been eclipsed. Rather, as Rosenberg’s superb prose indicated so clearly, its chief tenet, that of deconstructing the historical purpose and social meaning of art and embracing aesthetics only in the actual language that it uses to dismantle its own history, is merely in its late and mature phase. In other words, postmodernism, as Rosenberg surveyed it so vividly from his lofty perch as The New Yorker magazine’s art critic from 1967 until his passing, is simply finally doing what modernism was always designed to do: render utter subjectivity as the sole arbiter of any expressive visual language.

Thursday, July 22, 2021

Reality Redux: The Elegiac Paintings of Heather McLeod

“Painting is the representation of visible forms. The essence of realism is the negation of the ideal.”– Gustave Courbet, 1830.

Given the almost vertiginous diversity for self-expression available to contemporary visual artists in this day and age, I never tire of pointing out that far from being a million different subjects and themes for them to explore, or a million different formats for them to utilize in the execution of their works, there are in fact only four of each. Always have been, always will be. There’s something a little reassuring in this stylistic consistency and yet also a little daunting, given that every artist wakes up in the morning with art history breathing down their neck. So then, subjects and themes: self, society, nature, spirituality. Formats and delivery systems: portrait, still life, landscape, abstract. All the other aesthetic style vehicles can be distilled down to these two basic formal groupings, no matter how divergent or drastically experimental they might become. Also, whether the medium is painting or photography, cinema or video, installation or digital, is beside the point since these subjects and themes are embedded in the proportional harmony of our DNA via the golden section, and thus are impossible to evade, even if we wanted to do so.

Wednesday, May 26, 2021

How to Throw Your Voice Visually: Becoming Photography

|

| Chuck Samuels: Becoming Photography (Kerber Verlag, 2021). |

“From the idea that the self is not given to us, I think there is only one practical consequence: we have to create ourselves as a work of art.” – Michel Foucault

Much of what we now define as the poetics of images, the aesthetics of the camera, and the politics of photography comes to us from the thoughtful pens of cultural theorists such as the German critic Walter Benjamin, the French philosopher Roland Barthes, the American polemicist Susan Sontag, and the British art historian John Berger. Their speculations on what makes photography not only an art form but a special and privileged form of modernist consciousness have paved the way for a deep appreciation of both the magic potential and the seductive powers of technological reproduction. Our ways of seeing and thinking about seeing have often been guided by their ruminations on what happens when we photograph something or someone, and their penetrating analysis of the photographic arts has inspired and influenced generations of image-makers.

Wednesday, March 10, 2021

Found in Translation: Across a Bridge of Words

|

| left: Marina Tsvetaeva, 1925. (Photo: Roger Viollet); right: Nina Kossman (Photo: courtesy of American Pushkin Society) |

“A real translation is transparent; it does not cover the original, does not block its light, but allows the pure language, as though reinforced by its own medium, to shine upon the original all the more fully.” – Walter Benjamin, “The Task of the Translator,” 1921.

The Poets & Traitors Press series "seeks to showcase authors who travel between writing and translation" and "views translation as forming part of a continuum with the creative writer’s work". This imprint series began in 2013 and arose from the New York New School's translation workshop readings, which explored a shared format: featuring the original poems of translators of major poets alongside their translations of writers with whom they share a deep poetic resonance. Other Shepherds is the fifth book from Poets & Traitors, an independent press which continues to offer intriguingly hybrid books of poetry in conversation by a single author-translator.

Wednesday, October 7, 2020

Elemental: New Glass/Metal Paintings by Michael Burges at Odon Wagner Gallery, Toronto

|

| No 2. (2020), acrylic, Plexiglas, goldleaf on aluminum, 8 x 8 inches (Odon Wagner Gallery). |

“If we keep our eyes open in a totally dark place, a certain sense of privation is experienced. The organ is abandoned to itself, it retires into itself. That stimulating and grateful contact is wanting by means of which it is connected with the external world.” – Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Theory of Colours (1810).

Some viewers and readers may recall earlier bodies of work by Michael Burges executed in reverse painting on glass, a resistant surface which allowed us to look through to get at, and an intriguing strategy devised to liberate the artist from the acres of textile and canvas customarily used by painters throughout art history, those who formally celebrated its absorbent and tactile qualities. With these new works, this painter continues to explore reverse glass painting mounted on aluminum, an equally resistant and reflective surface capable of carrying the subtle language of his images of time-soaked light as a most effective medium. Our eyes themselves are now the delicate textiles which absorb their fleeting messages, if we allow their mesmerizing gaze back at us.

Wednesday, September 9, 2020

Memo from the Future: The Trans-Temporal Work of Kirk Tougas

This article first appeared in the Spanish film magazine Found Footage, March 2020.

“The assertion for an art released from images, not simply from old representation but from the new tension between naked presence and the writing of history on things; released at the same time from the tension between the operations of art and social forms of resemblance and recognition. An art entirely separate from the social commerce of imagery.” – Jacques Ranciere, The Future of the Image (2003).Every film is a tattoo etched on the surface of time, some more so than others. Certain filmmakers, however, eschew entirely the tradition of distracting the audience from awareness of the fact that they are watching and are customarily invited to submit to a wilful disappearance into a real or life-like story. These consummate others instead tend to invite the audience to relish and savour the viewing experience as a sequence of electric paintings, which may or may not contain a program beyond the temporary tattoo incised onto the dream space they occupy while in a theatre. Some of them, such as Kirk Tougas, go even further: they implore the viewer to actively engage in watching their own watching.

“When is appropriation appropriate?” – Kirk Tougas, 2019.

Tuesday, August 11, 2020

Time-Ghost: Art After Andy – The Biography of Andy Warhol by Blake Gopnik

“Images, our great and primitive passion . . .”Some artists loom so large on our cultural landscape that their shadow covers everyone who comes after them, and indeed, some heavyweights even obscure the very aesthetic horizon that they themselves helped to construct. The artists of the 20th century who can be said to be so influential and impactful, so important to the vernacular we use to even discuss art now, that their presence made possible the clearings in which whole clusters of others congregate stylistically can almost be counted on the fingers of one hand. Naturally enough, which fingers depends on which hand, but after much consideration it seems plausible that a scant few were so gargantuan in their production of new visual values that one can literally trace the branches of the artistic family trees they planted.

“The dream has grown gray. The gray coating of dust on things is its best part. Dreams are now a shortcut to banality. Technology consigns the outer image of things to a long farewell, like banknotes that are bound to lose their value. It is then that the hand retrieves the outer cast in dreams and, even as they are slipping away, makes contact with familiar contours. Which side does an object turn toward dreams? What point is its most decrepit? It is the side worn through by habit and patched with cheap maxims. The side which things turn toward the dream is kitsch.”

– Dream Kitsch, Walter Benjamin ca. 1930.

On my own hand there are five such titans: Cézanne, Picasso, Duchamp, Giacometti and Warhol. I realize they all happen to be white male artists, but I can’t help that, even though I can with absolute confidence also proffer Frida Kahlo, Lee Miller, Louise Nevelson, Eva Hesse and Judy Chicago as exemplary exponents of a feminist ethos of nearly equivalent prowess. But they, like many other practitioners in either gender, tend to work in fields originally germinated by those first five I mentioned. So I apologize in advance to all my many feminist friends and accept full responsibility for the personal biases of my own critical judgments. We do what we can within the limited scope of our own frail faculties and hope to be forgiven for unintended oversights.

Wednesday, June 3, 2020

Fabula: Transgression and Transformation in the Work of Müller and Giradet

|

| Contre-Jour (Backlight) 2009/Festival of Gijon, 2010. |

Note: A shorter version of this article appeared in Arcade Project Magazine on May 25, 2020.

“Images, our great and primitive passion . . .” – Walter Benjamin, ca. 1935.

“Your camera is the best critic there is. Critics never see as much as the camera does. The camera is more perceptive than the human eye.” – Douglas Sirk, 1955.

The two members of this creative pair of collaborating film artists are also visual archaeologists, conducting a rich excavation at the site of cinematic mythology. Sometimes a meaning is lost in translation, other times its essence is found in translation. In the case of the contemplative film experiments of Matthias Müller and Christoph Giradet, the immediately familiar territory of conventional storytelling, the art of fabula, and those cinematic stereotypes most often utilized in order to register meaning and emotion, have been translated from pure entertainment into pure reverie. None of the unconscious content embedded in their sources, however, has been left behind. On the contrary, as they explore the virtual edges of our visual domain in their compelling and challenging works, we are thrust into a jarring juxtaposition of painting, photography, storytelling and dreaming with our eyes wide open.