|

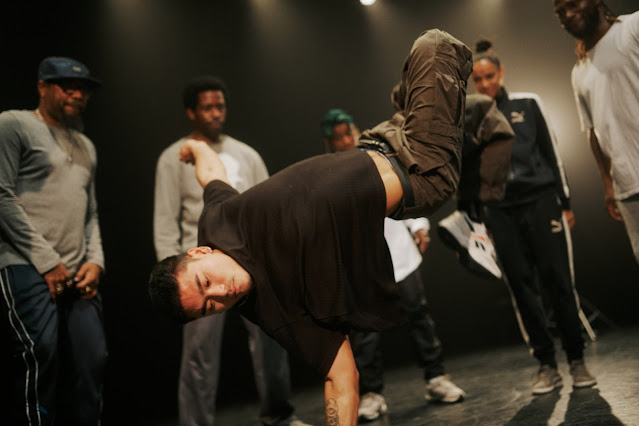

| Nima Rakhshanifar and Henry Stram in Andy Warhol in Iran. (Photo: Daniel Rader) |

The first play to be mounted on Barrington Stage Company’s St. Germain stage in three years is a two-hander, Andy Warhol in Iran, inspired by the artist’s 1976 trip to Tehran to snap Polaroids of the Empress Farah Pahlavi, the Shah’s wife, in preparation for painting her portrait. (Barrington Stage commissioned the piece, which is one of several new plays promised in this post-COVID season.) The two characters are Warhol – played by Henry Stram, who appeared in Richard Jones’s productions of The Hairy Ape and Judgment Day at the Park Avenue Armory – and a revolutionary named Farhad (Nima Rakhshanifar). Farhad is part of a group that hatches the idea of kidnaping Warhol from his hotel room and holding him hostage as a way of telegraphing their cause. Their scheme isn’t worked out very well, and neither, I have to say, is the plot of Brent Askari’s play, where the kidnaping is implausibly amateurish (Farhad wields a toy gun painted to make it look less obvious) and Warhol continues to cower in fear even after he figures out that he’s in absolutely no danger.