|

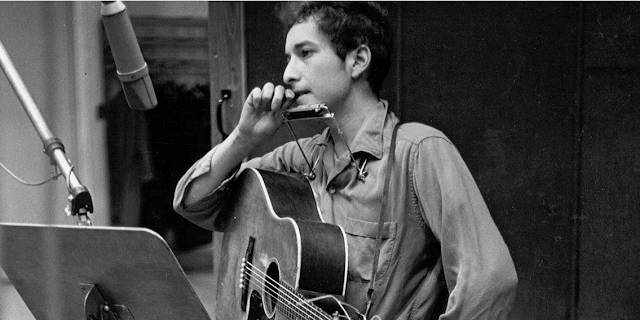

| Bob Dylan, November 1961. (Photo: Michael Ochs) |

I.

Many things matter about Folk Music: A Bob Dylan Biography in Seven Songs (Yale University Press; 273 pp.), Greil Marcus’s fourth—and, he has said, last—book about its subject. But your personal allegiance to Dylan in recent times isn’t one of those things. Whether you particularly value or even like the songs Marcus studies—in order of presentation, “Blowin’ in the Wind” (1962), “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll” (1964), “Ain’t Talkin’” (2006), “The Times They Are A-Changin’” (1964), “Desolation Row” (1965), “Jim Jones” (1992), and “Murder Most Foul” (2020)—also doesn’t matter. The Dylan we surveil in these pages is not the sum of his successes or failures, or of any reader’s likes or dislikes. He is a creative force, a dark, hunched, music-producing presence prowling through decades of celebrity and centuries of history. If you retain a nerve of commitment to anything Dylan has ever done or been, that will be your point of entry, and meanings will flow even from songs you never cared about—songs you may not care about now, except as vehicles for Marcus to do what he does best.

Dylan’s music is as deep in me as anyone’s, but it’s been a long time since I found him very interesting. That time stretches back to the millennium, when he punched out a clutch of works that in retrospect seem a last spasm of wild and generous surprise. These include Time Out of Mind (1997), an album about age and agelessness that I first experienced on a nighttime train ride and, not wishing to efface that memory, have never again played clear through; Masked and Anonymous (2003), which made me laugh when it was announced (“Jack Fate”?) but stunned me in the theater—for its explosive soundtrack, with Dylan holding his own against the young guns covering his classics, and for its fired-up cast creating a group action painting against an ever-shifting canvas; Chronicles, Volume One (2004), a memoir both deeply haunting and ridiculously entertaining, a book to be reread and relived forever; and present-day Dylan himself in the documentary No Direction Home (2005), a man smiling, telling tales, and leaving some of us wondering about the documentary that wasn’t made: the one that was nothing but him speaking.

Since then I’ve found the place where Dylan lives to be, in Marcus’s perfect phrase, a “plateau of heroic irrelevancy.” He gets respect for remaining obdurate, a challenge to my ability to find him bearable, even as one foundation after another has embraced him, prize committees have honored him, and museums have hung him. But the work is the work, and respect isn’t the same as pleasure. I haven’t cared about the albums of jazz and pop standards, Christmas carols, Sinatra favorites; nor, save a few songs, about the albums of original work that have followed Time Out of Mind. But I continue to care about what Greil Marcus makes of it all: the continuing adventures of this character he calls “Bob Dylan,” who is the picaresque hero of Folk Music.

Marcus writes that musical biography can be “not a key but a prison, a way of limiting what a song can say and where it can go by returning it always to its author, cutting the listener, the person to whom the song is actually addressed, out of the picture.” The brief opening section, titled “Biography,” collects facts of Dylan’s life and career so selectively that fact reads as untrustworthy, and far from the whole or most interesting story. It’s a gambit similar to the list of artists’ names that began The History of Rock ‘n’ Roll in 10 Songs (2014): a way of setting terms aslant, preparing the reader for other explorations. Folk Music pays biographical dues by giving age and year of death for each deceased person it mentions, and by drawing on the best evidence of when songs were first performed, published, recorded, and released. But Marcus’s subject is the more elusive issue of creativity and contingency in concert—how a piece of material or event is transformed by the artist, and how the results of that process interact with the living, making, and understanding of history. If fact can be an arrow pointing the way, it is never the way itself, let alone a substitute for thought and feeling about the true imprints that art and history leave on us.

If straightforward biography will not get at the sources of Dylan’s power, neither will the myth of intentionality. His own words on what he was thinking or attempting with a given song have typically been contradictory, obscure, or even untrue; to make them the only valid basis of interpretation is both to further deify the guru-genius and to evade the harder but more rewarding work of formulating personal response. Dylan’s power, Marcus prefers to believe, lies in “a sense of authorless authority” whose richest products, while singular in his hands, are always capable of changing shape in other hands. That’s one thing great art does, it changes; and for Marcus, no musician has exemplified the principle more than Bob Dylan—or “Bob Dylan.”

|

| Joan Baez and Bob Dylan at the March on Washington, 28th August, 1963. (Photo: Rowland Scherman) |

II.

Like other unmistakable styles, Marcus’s comprises a long-evolved vocabulary of words and phrases, a set of constructs and convictions. Times when he has been less than fully engaged by his subject, or simply tired of it, there’s been more style apparent than author, more “Marcus” than Marcus (speaking of characters we invent out of their works). A handful of sentences in Folk Music read that way, but not many, and we forgive those because each sentence is a step toward something, and not every footfall needs to coax flowers from concrete. He has earned the right to use, and sometimes overuse, his favorite words (“ordinary,” “indelible,” “novelty”), and to call upon his themes as John Ford, at different times, would call upon the face and body of John Wayne or of Henry Fonda.

A Marcus sentence, with its thick clauses and muscled perhapses, asks us to perceive traces that are so deep in a work they are likely to be unconscious, even unknown, to the creator. Here is part of a paragraph on “Desolation Row,” which Marcus suggests may contain the image of a lynching that occurred in 1920, in Dylan’s birthplace of Duluth, Minnesota:

… the song is not about [that crime] any more than it is about Albert Einstein, Bette Davis, or the Titanic, all of which appear in it. But the connection of a specific, publicly historical event, even if hidden, or especially if hidden, and a possibly private version of a historical event, and their connection in turn to the idea of a haven of free speech and free identity called Desolation Row, a place not on any map, that can only be spoken of in metaphors and riddles, but at the same time is the only place where one can feel truly oneself and truly acknowledge others, may not be an illusion. And to follow that possible connection, drawing on knowledge of how people move through history, how they disappear from it as history is erased, and how, sometimes in history books, sometimes in movies or paintings or songs, history is reclaimed, restaged, and rewritten, you may have to speculate.

Reduced to its bones, the passage is this: “The connection … may not be an illusion. And to follow that possible connection … you may have to speculate.” The Duluth lynching may not “really” be there, going by fact or intention; but being Marcus’s co-speculator means living in the ellipses. It means paying attention, in this passage and elsewhere, to words like “map,” “history,” and “connection”; accepting the imaginative invitation (“it’s as if”); heeding images of flux and unboundedness (“floating in the air of the song”); and weighing the relative construction (“less [that] than [this]”) that seeks precision, but not exclusivity. For Marcus, living in the ellipses means finding new ways to describe musical sensation: “Each instrument makes a tone, and the tones shift against each other, like plates on the side of a ship if they moved with the shape of the water.” It means telling stories, building drama. “Something new is about to begin,” Marcus starts his description of Dylan singing the slave song “No More Auction Block” at The Gaslight Café in Greenwich Village in autumn 1962. If you’ve heard the recording, you call up its memory, and your memory is transformed by his language: “the feeling is unearthly, a hum that seems to have been in the air of history: the sound of bodies going back to dust, the hum of thousands of insects bringing people who once lived into the earth, a hum snatched out of that air and forced to hold still.”

The dramatic sense is inextricable in Marcus from the time-trip element. This is sprung by songs which enter the world at fixed points yet fuse with events beyond them. Though it was first performed months before the Cuban missile crisis of October 1962, “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” has always been heard as a direct, if abstract, response to that event. (Dylan himself has called it that. So much for intentionality.) To get inside “Bob Dylan’s Dream,” a haunting track from the same album, 1963’s Freewheelin’ (this book’s foundational text, perhaps; it also contains “Blowin’ in the Wind”), Marcus blazes a crooked trail of quotation and allusion which begins in 1963, leaps forward to a night in 2001, then to two nights later, then to 21 years earlier, then to 39 years later. The mystery and meaning of this time-circuit lie not in Dylan’s words or performances but in Marcus’s arrangement of them, his chronologizing as an interpretive act; but through it all the dream song plays, echoing in its passages, forming a line that is also, somehow, a circle. “It doesn’t really matter where a song comes from. It just matters where it takes you,” Dylan says. But in the Marcus analysis, place, time, and timing may matter very much. They’re direct evidence of how songs—so many songs, not just Dylan’s—can slip in and out of time, not stopping the clock but melting it. And that’s a kind of magic that only art, history, and criticism, working together, can pull off.

|

| Bob Dylan, Greenwich Village 1970. (Photo: John Cohen) |

III.

“Blowin’ in the Wind” attracts Marcus in numerous ways. For him, it has evolved over six decades from pious simplism to ancient and “authorless” folk song. Ironically, given that its melody derives from “No More Auction Block,” it was the subject, early on, of a spurious controversy over authorship, which Marcus makes as enthralling as a detective story. (Sometimes great writing is just having a good tale and knowing how to tell it.) The song enables Marcus to quote extensively from the Little Sandy Review, a legendary pamphlet of folk-music criticism produced in the early sixties by Dylan associates in Minneapolis: he delights in the handmade, mainstream-resistant Review as he has before in Situationist tracts, punk zines, and other guerrilla publications. As metaphor, “Blowin’ in the Wind” offers plenty of pasture to roam in. “I still say it’s in the wind,” the young Dylan is quoted, “and just like a restless piece of paper it’s got to come down some time . . . and then it flies away.” Marcus has always seen history that way—as a windswept day-old newspaper, a mystery train, a continuity of ghosts. This song, like others he has tracked over the years, can never rest; its metaphor can never be satisfied. Soon after May 25, 2020, someone posts the song’s key lyric on a pole in Minneapolis, where it is spotted by Minnesota state representative Ruth Richardson, who invokes it when she says: “People talk about our system being broken. Our systems are working just the way that they were designed to work.” Like all beautiful metaphors, “Blowin’ in the Wind” is also ruthless, a vampire: it stays young on others’ blood, it lives because George Floyd dies.

The next chapter parallels “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll” with Laurie Anderson’s “O Superman,” a song Marcus has been trying to get his mind around since it appeared more than 40 years ago. His chain of meaning goes from Dylan to Anderson to Black American tenor Charles Holland, an expatriate singing in 1940 a French operatic piece from 1855, back to Anderson creating her piece in 1981, then to Anderson after 9/11, when events had given new import to some of her lines: “Here come the planes . . . they’re American planes . . . made in America . . . smoking.” Then, because he happens to have seen Fleetwood Mac in concert on a certain night, Marcus can bring it home with Lindsey Buckingham’s quotation of a line from Anderson’s song. (And another link is added to the chain by the co-author of a classic called “The Chain.”) Again, your own differing tastes do not restrict you from excitedly following the links as they are formed. I find “O Superman” a beguiling oddity, a tissue of thin sounds and thinner ironies. What is absorbing is the treatment Marcus writes of the movie that the song places in his head. Its key lies in the chapter’s opening paragraphs, which describe what, for Marcus and his generation of writer-fans, was the “simple, obvious, and overwhelming” relationship between music and politics—indeed, between every aspect of life and every other.

Writing about “Ain’t Talkin’,” the lengthy ballad that closed out 2006’s Modern Times, Marcus again demonstrates the power of an idea to reshape, even to supersede, its object. “You can picture a figure crossing a Great War battlefield . . . walking on bodies,” Marcus tells us he sees, in a description of the thing that is far more interesting, to me, than the thing itself. “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall,” another long doomsday ballad, emerges as the song within the song; not stopping there, Marcus quotes musicologist Steven Rings’s argument that the verse structure of “Hard Rain” was inspired by (not “reminiscent of,” not “resonant with,” but directly based on) Roy Orbison’s “Running Scared”—which then emerges as the song within the song within the song. The guiding arrow of “Ain’t Talkin’” is found in its affectless refrain, “a rhyme so embedded in American English that you can imagine John Smith mouthing it to himself as he took his first steps into Virginia: ‘Ain’t talkin’, just walkin’.” Marcus darkens the picture: “Walk, talk: it’s not a phrase, it’s a gesture, a posture, a way of carrying yourself that speaks of foreboding and escape.” Following that arrow to the image’s far but not final frontier, we encounter blackface minstrelsy, the forgotten fifties singer Jack Scott, the American tradition of deadpan humor, and the deathless voice of Fats Domino.

Marcus burrows into Dylan’s version of the Australian prison ballad “Jim Jones” through a long passage on Mike Seeger, brother of Pete, likewise scion of a family of Communists and musicians, who impressed the young Bob Dylan with his monkish devotion to folk music and culture. Marcus’s practice has always been to take a step back from his subject, then another, then another, the better to square up or take in the thing that is nominally in front of him. So he synopsizes someone’s novel in order to set up a song he once heard sung in a classroom, a performance which gave its deliverer a sense of transport similar to the sense that Marcus imagines possessed Mike Seeger—who he is using as a way into “Jim Jones”—which is a way into Bob Dylan—who is a way into folk music, which is really Marcus’s subject. Everything is an underground passage to something else. And “Jim Jones” is another chapter which doesn’t put me in love with the song; certainly, I don’t need to hear the many live versions from 1993 that Marcus describes, or measure my estimation of that evolution against his. Is this a failure on his part? Shouldn't he make me want to listen? Not necessarily. Reading the pages on “Jim Jones,” I care; I enter the picture; I itch with aliveness. What could be the failure in that?

|

| Bob Dylan, 2015. (Photo: Michael Kovac) |

IV.

To the extent that Folk Music has a deficiency worth mentioning, it is that Marcus pegs empathy, “the desire and the ability to enter other lives,” as Dylan’s secret power—the “key to his work” and “engine of his songs . . . the quality that defines Dylan’s music in its most uncanny moments.” It’s a counterintuitive perception of this artist, who, in the folk tradition, has often sung songs in others’ voices, but who came into greatness only when he found his own. The compulsion to remake another’s experience in one’s own eccentric terms is different from what we typically understand as empathy, and Marcus must know this: again and again in Folk Music, the line of exploration moves toward Dylan’s transformation of traditional songs (“No More Auction Block”) and documentary material (“Hattie Carroll”) to fit his voice, express his art. The second half of the “desire” line quoted just above speaks of Dylan’s ability “even to restage and re-enact the dramas others have played out, in search of different endings.” Again, not the same as empathy.

After introducing the word early on, Marcus, caught up in excursions that have led him in more fruitful directions, mentions empathy only seldom. By the final chapter, which pushes the theme a bit harder, irretrievable doubts have set in about how justly the idea of empathy, and the virtues it suggests, can be applied to this artist. I, at least, have never heard Dylan as an artist of empathy; when he says, in Chronicles, “I wasn’t too concerned about people, their motives,” I believe him. I suspect his real power, beyond an extraordinary and underappreciated gift for melody, is a pair of X-ray eyes. Dylan never stepped into anyone else’s shoes in his life. Instead, he kept his distance and studied people. He saw the faces beneath their masks, sometimes the masks beneath their masks. He saw that the president was a porn star, the civic leader a whoremaster, the American parade a lynching party: “the real Jekyll and Hyde themes of the times,” as he puts it, again in Chronicles.

Dylan, Marcus says, is “passing on something that was passed on to him—but in a queer way.” That queerness, it seems to me, is closer to being the key, if there is one, to Dylan as folk artist, because it implies metamorphosis. (And Ovid appears to be one of Dylan’s favorite poets.) His true biography, which Marcus would convince us lies in “his inhabiting of other people’s lives,” may more plausibly lie in his absorption of everything around him into a landscape and vernacular that are entirely his own. Dylan saw the world as he says Genet saw it: “as a mammoth cathouse where chaos rules the universe, where man is alone and abandoned in a meaningless cosmos.” He had what he attributes to Genet, “a certain consciousness of madness at work,” and the ability to coil that perception, rattler-like, inside tunes that people couldn't resist singing, changing—hearing back in their voices.

Yet this weakness of construct is another thing that doesn’t matter about Folk Music. The book builds on Marcus’s enduring theme of the democratic ideal finding form in musical versions of “everyday talk.” As each person is capable of changing history by acting within it, each song is “a failed or a successful attempt to dramatize life . . . if you listen that way, then no song is simple. No song is just a song.” The point is never whether his interpretation invalidates or argues down yours or anyone else’s; Marcus doesn’t practice criticism as a competitive sport. The point is watching him tease out multiple intangibles while fixing them on the page in precise yet poetic language. “I shot an arrow into the air, / It fell to earth I know not where,” goes a line from Longfellow: Marcus quotes it, referring to Dylan’s ability to implant songs, moments, and meanings that will take root in unknown places, grow in unforeseeable ways. But Marcus is as much the archer as Dylan. While the visible purpose of his work has always been to illuminate artists, works, movements, and histories, his implicit goal has been to loft his own arrows of meaning, and let them land where they would.

He has always extolled the creative value of openness, the promise of possibility, adventure, disruption, transformation—contingency, to use another of his magic words. It is a creed of hope and a version of free enterprise, founded on the American mythos of ambition and enormity. For fresh breaths of that freedom, he has often returned to books like Moby-Dick, The Great Gatsby, Constance Rourke’s American Humor, and D.H. Lawrence’s Studies in Classic American Literature, all of which are referenced in Folk Music. Presumably Chronicles occupies the same shelf in Marcus’s mind, for Folk Music is, among other things, a version of Dylan’s memoir, an extended sojourn in the terrain it creates. Both books are full of digressions and discursions, with Marcus the historian using footnotes for the same anecdotal tangents that Dylan the memoirist feeds right into his text. Folk Music moves backward and forward in time, its chapter sequence and chains of meaning usually privileging association over causality, each section based on a specificity—for Marcus, a song; for Dylan, a place or moment—which opens onto vistas of memory and muse. “All these songs about roses growing out of people’s brains and lovers who are really geese and swans who turn into angels”: that’s how Dylan, in words Marcus has often quoted, once described folk music. That mystery of recombination and reemergence is what Marcus has always found in Dylan, and so it’s not surprising that Folk Music is drenched in quotation from Chronicles, which Marcus calls “a kind of dream of folk music.” If Chronicles is a dream of folk music, it is also a dream of Folk Music, the book we’re reading now; or, to turn it right side round, Folk Music is a dream of Chronicles—a critic’s dream of an artist’s dream, the rose of one growing from the brain of the other.

What dismayed me most about Dylan’s Philosophy of Modern Song was its narrowness. It spoke in the voice and expressed the spirit of one who had internalized much of the scapegoating, victim-blaming, misogynistic, don’t-tread-on-me worst of American history. It made not only the present but also the past feel smaller, meaner, the rightful province of a few. Folk Music is a blessed corrective—not because it reminds us of a time when Bob Dylan wasn’t as ugly as he now makes himself sound, but because it reminds us of what a marvelous addition to American critical literature Greil Marcus’s “Bob Dylan” has been, and is. The book's openness restores a sense of existential unity, of a whole in which everything has a place and plays a part. It harmonizes with the scene in Chronicles that was set in the Louisiana souvenir shop of an old man named Sun Pie, who upon Dylan’s entrance began discoursing on anything that came to his mind. Listening, Dylan noted the posters on Sun Pie’s wall, and the songs that played on his radio: The Beatles’ “Do You Want to Know a Secret,” Dale and Grace’s “I’m Leaving It All Up to You,” Phil Phillips’s “Sea of Love.” Not one of the songs felt arbitrary, empty of implication for the offbeat scene before us. You felt bathed for a moment in a sea of love, song, and symbol, its components—of which you were one—shifting “like plates on the side of a ship if they moved with the shape of the water.” You felt again that no two things, people, or pieces of history are unrelated, are ever strangers. You realized again that it’s all folk music.

– Devin McKinney is the author of Magic Circles: The Beatles in Dream and History (2003), The Man Who Saw a Ghost: The Life and Work of Henry Fonda (2012), and Jesusmania! The Bootleg Superstar of Gettysburg College (2016). Formerly a music columnist (The American Prospect), blogger (Hey Dullblog), and TV writer (The Food Network), he has appeared in numerous publications and contributes regularly to Critics At Large and the pop culture site HiLobrow. He is employed as an archivist at Gettysburg College in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, where he lives with his wife and their three cats. His website is devinmckinney.com.

Devin: Donald Brackett here, kudos on your excellent piece on this master, where even the things you take issue with are analyzed with acumen and clarity. Thanks also for the in-depth length and breadth of your work concerning his deeply important work. Cheers, D.

ReplyDelete