|

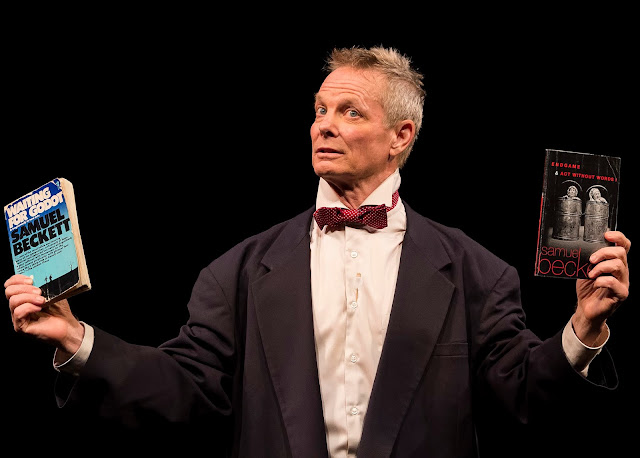

| Bill Irwin in On Beckett. (Photo: Craig Schwartz) |

At the top of On Beckett, the one-man show Bill Irwin brought to Boston last week in the Arts Emerson series at the Emerson Paramount Theatre, the star tips and slightly rumples his bowler, bends his knees, throws his weight onto his ankles, stoops, leans forward and bears down on his left shoulder. All of these adjustments take merely a few seconds, yet he’s transformed utterly, and you think you’re in for a mesmerizing evening that brings together this actor’s clown gifts and his profound understanding of Samuel Beckett, whom he has been studying for half a century and whose work he famously takes tremendous pleasure in performing. I saw Irwin play Vladimir in a revival of Waiting for Godot on Broadway in 2009, opposite Nathan Lane as Estragon, and he was brilliant; the whole cast was. (John Goodman and John Glover played Pozzo and Lucky.) So these preparatory moments, after a somewhat overlong introduction, filled me with happy anticipation.

They were also, I’m afraid, the only ones I can honestly say I enjoyed in the uninterrupted ninety-five minutes of On Beckett. The program promises passages from Godot as well as three non-dramatic works, Texts for Nothing, The Unnamable and Watt. But fully three-quarters of it is an extended lecture on the writer, and except for the odd witticism it’s insufferable: inflated, pompous, with pauses for name-dropping (Irwin makes a meal of the litany of stars he’s appeared with in various productions of Godot, beginning, of course, with Robin Williams and Steve Martin in the Mike Nichols version). Occasionally he’s even combative. The most salient example is an insert where he challenges anyone who’s imperceptive enough to have missed Godot’s political subtext. I confess myself to be among those pathetic ignoramuses, but I don’t think I’d mind being called an idiot if Irwin had the grace to make a joke of it. But he’s deadly serious, even when he wants you to think he’s cracking wise: he wants us all to genuflect before his scholarly acumen and superior experience.

If it sounds like I’m complaining because On Beckett didn’t contain enough actual Beckett, let me correct that impression. The lectures were almost a relief from the tedium of the performances, in which Irwin does any number of clever things with his body and his voice but never once makes an actor’s – or a clown’s – sense of them. Pauline Kael once wrote about Marlon Brando, “He’s an actor: when he shows you something, he lets you know what it means.” Watching and listening to Irwin’s Beckett bits, I didn’t have a clue what he was talking about or what we were supposed to make of these pieces. In Stanislavski’s An Actor Prepares the teacher Tortsov criticizes one of his students for displaying her pretty legs for the audience’s enjoyment; Irwin wants us to admire the flexibility of his body (which is certainly amazing) and all the tricks he can play with his voice. And because it’s all show without meaning, it’s so remote that I didn’t feel a thing. Years ago I saw Billie Whitelaw perform Beckett’s monodrama Rockaby live in a college auditorium, and when it was over I felt as if I hadn’t breathed while it was going on. The hour was emotionally overpowering; I could barely speak when she was done. During the performance parts of On Beckett I felt numb.

I loved Irwin’s clown show Largely New York, and I thought he was very fine in Jonathan Demme’s Rachel Getting Married, which gave him the largest role he’s had on screen. But there are two Bill Irwins. The first time I encountered the other one was in a Broadway revival of Bye Bye Birdie during the season following his triumphant Vladimir in Godot. It was a blighted production from start to finish, but Irwin, playing Harry MacAfee, the ulcerated father of the teenage girl who’s been chosen to kiss Conrad Birdie on The Ed Sullivan Show before he departs for the army, was the worst thing about it. He didn’t seem to care that he was playing in a style unlike anyone else's, and not a stick of furniture escaped his relentless scenery chewing. It was that same self-indulgent Bill Irwin who took the stage in On Beckett. Would the other Irwin kindly come back?

– Steve Vineberg

is Distinguished Professor of the Arts and Humanities at College of the

Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts, where he teaches theatre and

film. He also writes for The Threepenny Review and is the author of

three books: Method Actors: Three Generations of an American Acting Style; No Surprises, Please: Movies in the Reagan Decade; and High Comedy in American Movies.

– Steve Vineberg

is Distinguished Professor of the Arts and Humanities at College of the

Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts, where he teaches theatre and

film. He also writes for The Threepenny Review and is the author of

three books: Method Actors: Three Generations of an American Acting Style; No Surprises, Please: Movies in the Reagan Decade; and High Comedy in American Movies.

No comments:

Post a Comment